Hyperspectral Imaging Provides Real-Time 3D Visualization

By combining multiple passive and active sensors, autonomous systems gain real-time, actionable intelligence, enabling them to respond dynamically to their changing environments.

By Trond Løke

With recent breakthroughs in computational power and real-time processing, hyperspectral imaging — long a cornerstone of remote sensing — is entering a new era where data analysis and visualization occur simultaneously. This technology, which captures a continuous spectrum of light across hundreds of narrow bands, has transformed industries such as mining, agriculture, defense, and environmental monitoring. Now, critical information and actionable intelligence can be produced in real time directly from the hyperspectral sensor that is on board small UAVs,

which can be shared with users or used by other autonomous systems. This capability enables faster decision-making and operational efficiency, unlocking possibilities for real-time situational awareness and automated responses.

A HySpex Mjolnir VS-620 navigation system with lidar, flying on an Acecore NOA6 UAV equipped with a tilted AEVO Gremsy gimbal, looking into the tree line. Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

The basics of the technique

Hyperspectral imaging enables precise material identification by leveraging the unique spectral signatures of objects. Unlike traditional imaging systems that capture only three broad bands (RGB), hyperspectral cameras collect hundreds of spectral bands, and the resulting data offers unprecedented insight into material composition. This capability is invaluable in applications such as geological surveying, mineral detection, and precision farming. However, the ultimate potential of hyperspectral imaging depends on the incorporation of sophisticated data processing techniques, including georeferencing, atmospheric correction, and spectral classification.

For any remote sensing system,

accurate georeferencing — the alignment of a digital map with actual geographic locations — is crucial. It requires the surface geometry to be obtained to accurately map pixels from the sensor to real-world coordinates. A digital surface model is typically generated using lidar or photogrammetry. Another key challenge is atmospheric correction — converting at-sensor radiance into accurate surface reflectance values. This process compensates for atmospheric losses due to scattering and absorptions, as well as geometric effects caused by the terrain, such as slope, reillumination from surrounding terrain, and shadowing.

Modern innovations have refined hyperspectral data processing, transforming raw at-sensor radiance into orthorectified hyperspectral cubes with precision. The processing time for these tasks has dramatically improved during the past 20 years due to the speed of CPUs and GPUs, evolving from weeks of computation to near-

instantaneous results, even on UAV-compatible hardware. This article explores how real-time performance has been achieved in the process of imaging to actionable results, and the implications for various industries.

Evolution of real-time processing

During the past few decades, computational advancements have revolutionized data processing for these real-world scenarios. The weight-to-power efficiency of modern processors has

increased, enabling complex calculations to be executed on airborne platforms, including UAVs. Companies such as HySpex, NORCE, Prediktera, and ReSe are leveraging these advancements to develop an integrated solution that enables real-time hyperspectral imaging and processing on board a drone.

Trond Løke prepares a full UAV system for a demo flight at a copper mine in Arizona.

Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

Some of these innovations have been a product of the European Union’s Horizon Europe program under the m4mining project. The goal of m4mining is to enhance material characterization during exploration, extraction, re-mining, and environmental impact assessments. The consortium, which includes Norsk Elektro Optikk AS, NORCE, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, Prediktera AB, ReSe Applications, the University of Queensland, University of Patras, Cyprus Geological Survey, and Luleå University of Technology, is working to develop hyperspectral-based solutions for real-time mineral classification and visualization.

Hardware innovations

For example, the HySpex UAV solution is adaptable to multiple platforms, from drones to stratospheric airships. The payload includes two hyperspectral cameras: The Mjolnir V-1240

(400 to 1000 nm) in the visible and near-infrared (VNIR) region of the spectrum, and the Mjolnir S-620

(950 to 2500 nm) in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) region.

These cameras are supported by a compact onboard computer, a high-performance navigation system, and a lidar for surface modeling. This combination enables precise real-time hyperspectral data processing from 3D surface reconstruction using lidar data via at-surface spectral reflectance to visualize the classified results.

One of the most notable challenges in hyperspectral imaging is spatial misregistration between different spectral bands. But cameras have been optimized to maintain a spatial misregistration of <10% of a pixel. A key difficulty is co-registering VNIR and SWIR imaging spectrometers, which have different sampling point spread functions (SPSFs). By carefully characterizing the SPSF of each camera, a resampling filter is applied that ensures spectral fidelity and favorable SPSF matching between the two sensors. Furthermore, raytracing techniques are used to align the pixel positions in 3D space, enhancing the accuracy of VNIR-SWIR fusion.

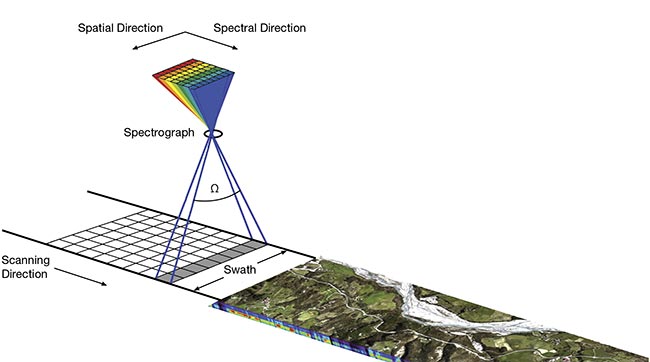

A schematic view of a push-broom hyperspectral system. Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

Advanced software

Conventional hyperspectral data post-processing, i.e., not in real time, involves several critical steps:

1) Raytracing and georeferencing: mapping each pixel to its real-world coordinates using a surface model that is generated via lidar or photogrammetry.

2) Atmospheric correction: adjusting for terrain effects such as reillumination, shadows, and atmospheric losses to obtain reliable reflectance values of the surfaces being imaged, without the use of reflectance targets.

3) Application-specific processing, such as spectral classification and anomaly detection.

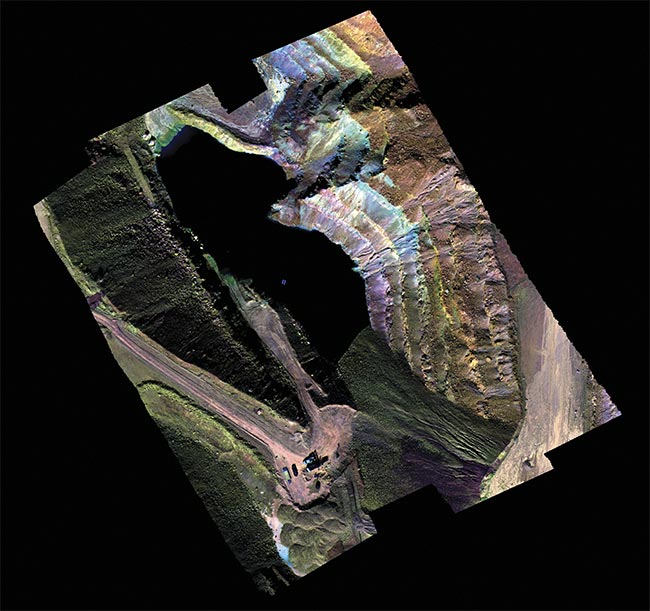

4) Data rasterization: Traditionally,

hyperspectral data is converted into a regular grid, but this introduces pixel loss, duplication, and significant data overhead.

Flight paths are never perfectly stable. Parameters such as roll, pitch, heading, speed, and altitude inevitably vary throughout the flight, which leads to irregular ground sampling distances in all directions.

The degree of instability differs between platforms. Generally, fixed-wing aircraft provide more stable flight characteristics compared with multi-

rotor drones. Stability improves further when platforms are equipped with active stabilizers or gimbals, but even with such systems, perfect stability is unattainable.

Another contributing factor to ground sampling distance variability is the combination of fixed-flight altitudes and changing surface elevations. When the terrain varies significantly relative to the flight altitude, the real pixel size across tracks fluctuates.

All of these factors introduce complications when attempting to rasterize the data into a grid with a fixed pixel size. An irregular ground sampling

distance is being forced into a regular grid, which can result in duplicated

or omitted pixels. This process introduces geometric distortions and can misrepresent small objects and edge features.

However, these rasterization issues diminish significantly at high altitudes, such as in spaceborne remote sensing, where platform stability and variations in distance to the ground are minimized.

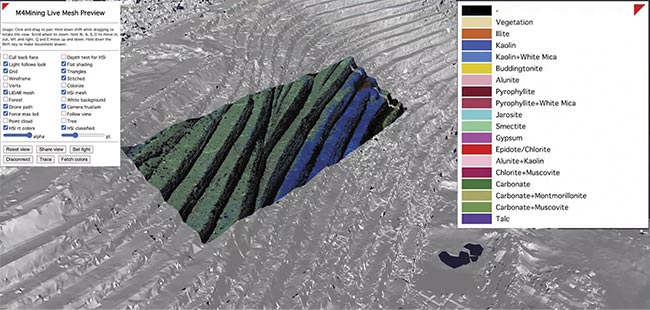

A screenshot of the 3D visualization software showing mineral maps of an open-pit mine in real time during flight. Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

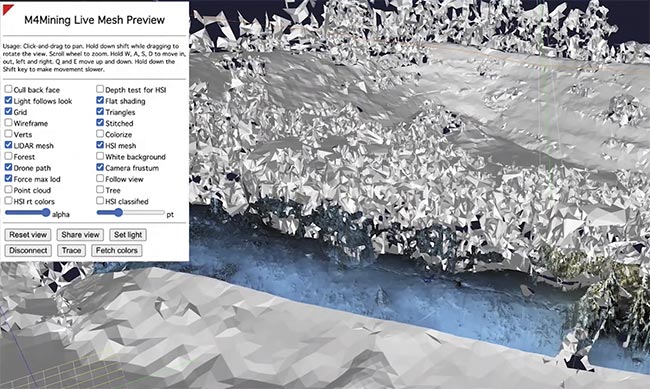

A screenshot of the 3D visualization software showing a false-color hypermesh on a real-time generated mesh from a lidar. Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

To overcome the limitations of rasterization, it is best to start from a point-cloud-based hyperspectral data structure. By preserving the x, y, and

z coordinates of each pixel, spatial

integrity is maintained while 3D visualization is enabled. However, point clouds alone lack spatial connectivity, making certain computations inefficient. The solution is a triangular

mesh representation, a so-called hypermesh.

The benefits of a triangular mesh representation of hyperspectral data include but are not limited to:

Efficient spatial calculations, such as nearest-neighbor searches and interpolation; adaptive resolution and seamless visualization at any zoom level, using GPU optimization for high-speed rendering; accurate surface representation, particularly for irregular terrain and 3D surfaces; and scalability, because it efficiently represents large data sets with fewer data points than regular grids.

In a hypermesh, each vertex is directly linked to the spectral data and each vertex corresponds to a known x, y, and z coordinate. In a mesh format, topological relationships between neighboring pixels are preserved. In the hypermesh format, pixel loss and duplications do not occur and it is directly compatible with rendering engines in browsers, for example. The mesh formats provide significant processing benefits, and graph-based algorithms can perform efficient neighborhood searches and segmentation, and processing hardware, such as GPUs, easily incorporates meshes.

Hyperspectral data management will likely deviate from rasterized formats in the future. As such, it will be important to minimize data overhead, achieving real-time processing and data visualization with <5% storage overhead beyond the raw data set.

Real-time scene reconstruction

A major hurdle in real-time hyperspectral imaging is the generation of digital surface models during UAV flights. These models are crucial for accurate 3D scene reconstruction. To address this, processing techniques have been developed that generate digital surface models in real time using the onboard lidar. The resulting models are used in a ray-tracing engine to produce high-resolution hypermeshes — 3D hyperspectral data sets ready for analysis and visualization.

An example of a rasterized image of an open-pit mine. Courtesy of HySpex by NEO.

Beyond 3D radiance data, real-time atmospheric correction is also performed. This ensures accurate reflectance measurements, which are used to create application-specific meshes in real time. Unlike traditional rasterization-based methods, this approach minimizes data storage requirements while maximizing visualization accuracy.

Uses of hyperspectral imaging

In the m4mining project, one of the most crucial algorithms implemented is the USGS MICA algorithm, which enables the detection of minerals using spectral libraries. The real-time processing component of Prediktera’s software is called Breeze Runtime, which plays a key role in the overall data pipeline.

Following the reflectance retrieval from the raw, geometry-merged data cube, the information is processed for application-specific analysis. In the m4mining project, this includes classifying minerals and generating various mineral meshes. These meshes, still in raw geometry, are transmitted to the ground station, where they are visualized as MineralMesh — a fully interactive 3D representation.

The potential for application-specific algorithms within this framework is vast. In mining, the real-time platform enables continuous updates of both the surface model of the entire mine and the mineral composition of active and inactive mine faces — multiple times per day. This enables real-time visualization of mineral content directly at the mine face, enabling early-stage sorting by excavators precisely at the point of extraction.

Beyond active operations, this technology also supports applications in exploration, re-mining, and environmental monitoring by delivering real-time data output. For instance, it can assist in tracking environmental impacts or identifying changes over time across the mining site.

In the domain of security and defense, hyperspectral imaging provides powerful capabilities such as real-time camouflage detection, anomaly identification, and classification of thermally neutral or low-emissivity objects. These outputs can take the form of target meshes based on anomaly detection, spectral signature matching of known materials, vegetation indices, or even moisture content meshes.

Environmental monitoring is another critical area of application. Hyperspectral systems can detect hydrocarbon leaks in real time — whether in liquid form, such as diesel spills from pipelines, or in gaseous form, such as methane, a potent greenhouse gas. These capabilities support early

warning systems for environmental hazards and help mitigate ecological damage.

In precision agriculture, hyperspectral imaging is changing how farmers monitor and manage crops. It enables early detection of plant diseases by identifying subtle spectral changes before visible symptoms appear. It can also assess nutrient deficiencies and plant stress with high accuracy, enabling targeted fertilization.

Additionally, it

supports weed and invasive species detection through spectral differentiation, facilitating more precise and sustainable weed control strategies.

These are just a few examples of how this groundbreaking technology is transforming industries; the applications are vast and growing.

The ability to process hyperspectral data in real time — without rasterization and with minimal data overhead — marks a significant leap forward in remote sensing. With integrated hardware and software solutions, the industry is pioneering real-time hyperspectral imaging that transforms raw sensor data into actionable 3D insights. Whether in mining, defense, agriculture, or elsewhere, real-time hyperspectral imaging is poised to revolutionize how the environment is perceived and interacted with.

The partners in the m4mining project will continue to advance real-time capabilities in hyperspectral imaging, both within similar initiatives and through new project formats. However, a key factor remains essential: collaboration between small- to medium-size enterprises, research institutions, and industry stakeholders is critical to delivering a solution that provides users with an effective and valuable experience.

Meet the author

Trond Løke has a master’s degree in photonics from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. He calibrated Norsk Elektro Optikk (NEO)’s first hyperspectral system in 2002 and helped design HySpex’s first hyperspectral imaging system in 2003, eventually becoming the CTO. In 2020, Løke became the CEO of NEO, located in Oslo, Norway; email: trond@neo.no.

/Buyers-Guide/HySpex-by-NEO/c30534