AI Is Driving Increased Deployment of Industrial Robots

Modern neural networks are aiding the ability of industrial robots to adapt to their surroundings in real time, reducing deployment time and increasing the number of deployments each year.

By David Bruce

In established industrial landscapes, such as automotive manufacturing and warehouse logistics, vision-language-action (VLA) models — which combine natural language understanding, computer vision scene understanding, and action command generation — offer the tantalizing

possibility of dramatically enhanced robotic system flexibility. This would enable a robotic arm that not only interprets human commands in natural language but also simultaneously uses visual feedback to adjust its actions in real time. Early demonstrations, such as those seen in vision language models such as RT-2 from Google DeepMind, show systems that integrate web-scale vision-language models with robotics demonstration data to interpret commands and generate action tokens that directly control physical hardware.

An industrial engineer works with AI automatic robotic arms in an intelligent factory. Courtesy of iStock.com/greenbutterfly.

These advancements suggest that AI can reduce the need for manual reprogramming, empowering robots to adapt quickly to dynamic production environments. However, current limitations in effectively tokenizing action data indicate that an additional five to 10 years of development may be needed before VLA models can be seamlessly integrated into existing industrial processes.

A foundation in AI

In the minds of many system developers, modern AI entered a new era

in 2012 when AlexNet (a deep convolutional neural network architecture) won the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge, which evaluated algorithms for object detection and image classification at large

scale (AlexNet was entered as SuperVision). AlexNet achieved a top-five error rate of 15.3% in the competition, beating the next submission by 10%. Competing algorithms were tested on images that had not previously been seen. Each algorithm provided its top five guesses as to which of the 1000 possible objects was present in each test image.

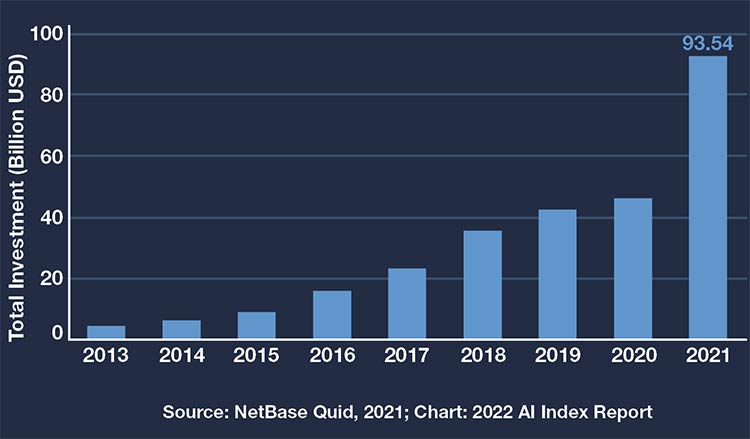

The exponential growth of investment in AI. Courtesy of Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI).

The chart above shows how private investment in AI began to grow after AlexNet’s transformational performance.

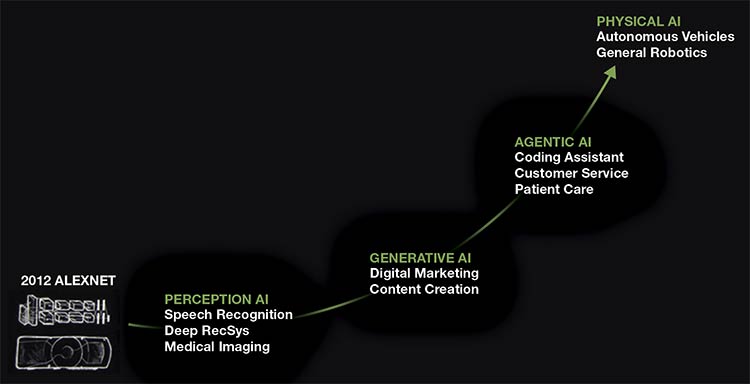

The screenshot below, from NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang’s keynote address at the GPU Technology Conference, shows how the current AI mania was catalyzed by AlexNet.

A graphic interpretation of the advancement of AI since the introduction of AlexNet. The upper right corner of this screen shot — “PHYSICAL AI” — represents the iteration with the potential to exponentially accelerate industrial robot deployment. Courtesy of NVIDIA.

AlexNet decisively proved for the first time that a neural network-based approach could solve a highly difficult problem that could not be solved by classical engineering approaches. The model demonstrated that a system that did not have prior knowledge of a problem could simply have data run through it, essentially teaching it what certain configurations of pixels represent to the human eye. AlexNet was a deep convolutional neural network using eight layers and 60 million trainable parameters. Many derivative versions of AlexNet emerged after 2012, adding layers and showing incredible performance in 2D image segmentation and object detection.

Deep convolutional neural networks enabled near real-time image classification and segmentation and could be considered the beginning of the modern AI revolution. The next notable advancement emerged from applying neural networks to language translation and natural language processing. A paper that was released in June 20171 introduced the transformer architecture, which proved to be highly effective at language translation and text generation based on prompts. The transformer has become the dominant neural network architecture used for solving many different problems, not just language translation. The transformer architecture introduced the concept of self-attention, which allows neural networks to capture long-range dependencies in large data sets while keeping the computation costs reasonable.

ChapGPT and all the current large AI models are based on the transformer architecture, which has been applied to language, speech recognition, image recognition, and segmentation. Transformers work by tokenizing a domain — for language, tokens include all the letters in a particular alphabet, parts of words, and whole words. All the possible relationships among these many tokens are learned through extensive model training, which can be unsupervised in language. If a domain can be tokenized, then a transformer-based model can be created to make predications within that domain and create content in the domain such as text, speech, pictures, and videos.

However, one domain where tokenization may not be straightforward is robotic movement, which includes position, velocity, and torque commands guided by continuous signals.

AI-driven tasks

Beyond traditional factory floors, the potential of VLA models lies in their ability to enable entirely new applications. In fields such as precision agriculture, health care, and search and rescue missions, robots enabled by VLA systems could perform tasks in highly unpredictable environments. Here, actions are not simply preprogrammed routines but responses cultivated from continuous sensor feedback and multimodal reasoning. While the appeal is undeniable, these sectors impose even more stringent demands for safety, adaptability, and real-time decision-making — challenges that may extend the timeline for meaningful adoption by 10 to 15 years, or more.

When it comes to action, especially in the context of physical robotics, the landscape is entirely different. Actions in real time involve continuous variables in robotic movement, such as joint angles, speeds, forces, and dynamic adjustments that have spatial and temporal dependencies. Converting these continuous operations into discrete tokens risks oversimplification of required actions and a lack of dynamic control. For instance, a sequence of action tokens might encode a robot’s end-effector position with a string such as “1 128 91 241 5 101 127 217,” where the numbers indicate a range of commands. However, unlike words, these numerical tokens represent a physical state that continuously evolves over time. The discretization process might lose critical nuances in action precision, leading to suboptimal control, where small errors can propagate into significant deviations — for example, incomplete processes in a manufacturing environment during task execution.

Unlike language — where the context remains relatively stable during sentence generation — robotic actions depend on real-time feedback from sensors and continuous action commands. Self-attention, although excellent at weighing the relative importance of different words or tokens, may struggle with the dynamic, continuous, and interdependent nature of physical actions. Even if the transformer model can capture a level of dependence between sequential actions, the inherent delay in processing and the inability to deal with the necessary temporal granularity in a specific setting might limit efficiency, obstructing the direct application of transformer architecture for real-world robotic control.

Barriers that remain

In the robotics community, many are aware that the primary hurdle for VLA models is the insufficient availability of high-quality, diverse robot demonstration data. In deep learning, more data often implies better generalization. The scarcity of comprehensive data sets for high-fidelity robotic tasks might mean that the current generation of VLA models cannot learn robustly across all required scenarios. Consequently, despite promising laboratory results, performance in industrial settings remains underwhelming.

And from a broader perspective, an even deeper concern arises: Perhaps the entire tokenization/self-attention paradigm, which works so effectively for language, may be fundamentally mismatched with the requirements of action generation. In language, tokens are fixed, symbolic representations that map neatly onto a finite vocabulary. However, actions in a physical world are inherently “fuzzy” and require representations that capture a continuum of movement and force. This discrepancy might indicate that even with more data, the transformer’s fundamental mechanism may be ill-suited for the nuanced predictions needed for continuous control. If so, rather than simply gathering more demonstration data, the robotics community might need to rethink the underlying architectural approach.

But proponents of applying transformers — that process sequential data — to robotics argue that the adaptability and generalization capabilities shown in pioneering models such as RT-2 could be harnessed and improved with tailored adjustments. For instance, tweaking the tokenization process to better capture continuous variables — perhaps by using hybrid representations that combine discrete tokens with continuous latent variables — could provide a bridge between the transformer’s strengths and the demands of real-time control. Additionally, integrating reinforcement learning with transformer-based architecture could allow the system to refine its action predictions based on feedback, gradually overcoming the limitations of a purely tokenized approach.

One potential pathway to more

robust performance is to explore

hybrid models that combine the strengths of transformers with other paradigms, such as graph neural

networks or recurrent architectures. Such models could leverage tokenization for parts of the task that lend

themselves to discrete representations, while using alternative methods to

process real-time sensor data and

continuous control signals. For instance, a neuro-symbolic integration could allow for the high-level reasoning provided by the transformer while

delegating low-level, high-precision control to specialized modules trained explicitly on reference trajectories and sensor feedback.

Another promising approach lies in integrating reinforcement learning frameworks with transformer-based VLA models. Reinforcement learning methods are inherently designed

for continuous control environments and can optimize actions based on direct feedback from the environment. Embedding a reinforcement learning module to interpret and refine the outputs of a transformer could enhance the system’s ability to handle the temporally precise and dynamic requirements of industrial robotics. This coalescence of learning approaches could more effectively capture the central nuances that a purely tokenized model overlooks.

As academic research and industrial stakeholders continue to refine VLA models, collaboration will be critical — not only in driving data collection efforts but also in establishing new standards for representing and processing action commands. By developing standardized protocols that more effectively translate continuous sensor information and motor commands into hybrid tokens, researchers can bridge the gap between the theoretical strengths of transformers and the practical demands of robotics control.

While VLA models hold transformative potential, realizing their promise in a robust, industrial context requires a paradigm shift. The debate of whether the transformer architecture’s self-attention and tokenization mechanisms can effectively operate for action generation is not merely an academic exercise. It is a foundational question that could drive the next wave of innovation in robotics. Researchers must remain open to the possibility that expecting transformers to work “out of the box” for robotics is overly optimistic. Instead, targeted research into hybrid models or entirely new architectures may pave the way for future breakthroughs.

Meet the author

David Bruce joined FANUC America Corp. in 1997 and is currently an engineering manager in the Robot Segment for a group of engineers that support FANUC robot integrators and end users with the application of FANUC’s fully integrated intelligent products. He has a master’s degree in computer science from Oakland University in Auburn Hills, Mich., and a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the University of Windsor in Ontario; email: david.bruce@fanucamerica.com.

Reference

1. A. Vaswani et al. (June 2017). Attention is all you need. 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, Calif.

/Buyers-Guide/FANUC-America-Corp/c4728

Published: September 2025

Glossary

- computer vision

- Computer vision enables computers to interpret and make decisions based on visual data, such as images and videos. It involves the development of algorithms, techniques, and systems that enable machines to gain an understanding of the visual world, similar to how humans perceive and interpret visual information.

Key aspects and tasks within computer vision include:

Image recognition: Identifying and categorizing objects, scenes, or patterns within images. This involves training...

Robotic Systems and EquipmentFeaturesAIroboticsVLA modelsautomotivecomputer visionDeepMindAlexNETconvolutional neural networksChatGPTNvidiatokenizationtransformerreinforcement learning