POLINA POTOCHEVSKA, EDITORIAL INTERN

Avocados are one of the most popular and versatile fruits today, and spreading them on toast is much easier than deciding when they’re ripe and ready for sale.

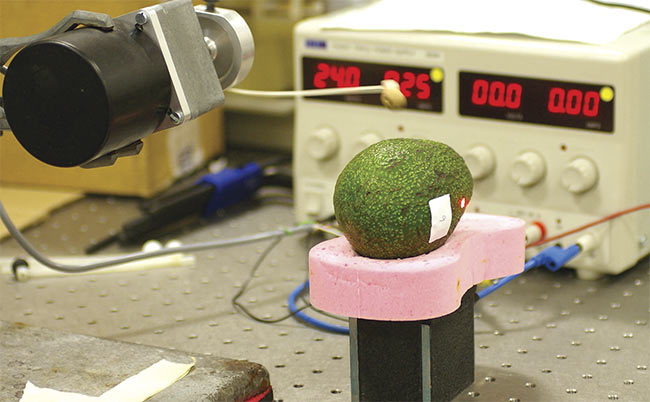

Can avocado science serve up more ripened fruit? Cranfield University professors Sandra Landahl and Leon Terry are adapting laser Doppler vibrometry to the task. Courtesy of Cranfield University.

The Waste and Resources Action Programme’s 2011 “Fruit and Vegetable Resource Maps” report estimates that almost a third of avocados are lost in the supply process in the United Kingdom, with about 2.5% to 5% lost as retail waste. More concerning is that today, avocado enthusiasts everywhere remain at risk of trying to convert rock-hard fruit into guacamole.

Thankfully, cutting-edge avocado science has developed a new nondestructive test method that promises to prevent consumers from ever again having to deal with an unripe avocado.

In a paper titled “Non-destructive discrimination of avocado fruit ripeness

using laser Doppler vibrometry,” Cranfield University professors Sandra Landahl and Leon Terry describe how they adapted a technique more familiar to the automotive industry to broaden the enjoyment of the fruit. Such nondestructive techniques for avocado inspection are in demand because of the amount of waste that occurs during grading, Landahl said in an interview with Photonics Media.

Applied to avocados, laser Doppler vibrometry (LDV) leverages a sensor that measures resonant frequency, in contrast to acoustic impulse response techniques that are often used in texture studies.

In their paper, Landahl and Terry describe LDV as being based on the Doppler effect, which is the frequency shift of waves backscattered from a moving

surface. Their test uses lasers to first mea-

sure the refracted light from an avocado. The researchers then measure the resonant frequency by applying energy such as a tap or a sound sweep to the fruit and using the fruit’s particular shape and softness to determine its level of ripeness. Landahl explained that resonant frequency depends on the stiffness of the object and is proportional to the dynamic elasticity modulus of the object. In other words, avocados send a distinguishable signal when ripe.

Before these specially developed techniques, avocados were a challenging fruit to test with LDV because of their irregular shape and rough skin, Landahl said. This type of LDV can be applied to other fruits and vegetables as well, although most easily to those with a similar shape to an avocado and that share a similar mass within a batch. LDV is also able to measure whether the fruit softens during ripening or after damage or pathogen decay.

Researchers elsewhere have successfully applied LDV to inspect other fruits, but Landahl did not know of any systems that had been commercialized. She said she hopes, however, that the method could be implemented with the help of dedicated fruit distribution houses and a grading line manufacturer. Should that day arrive, avocado lovers could rest easy that every avocado they select from the grocery store is ripe and ready to eat, guaranteed.