Liza Pretorius, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Services

While dentistry has become increasingly sophisticated, uncertainties still exist in the diagnosis and treatment of dental conditions that are left to the discretion of the practitioner. Part of the reason for this uncertainty is that the composition of teeth is not static. The structure and integrity of teeth vary with the chemical environment of the mouth and is influenced by various factors, including age, sex, and diet, in addition to endogenous and exogenous influences, such as acid reflux and medication use. Assessing such changes can be useful in guiding clinical interventions, and the use of spectroscopic tools, particularly those that operate in the near-infrared (NIR) range of the spectrum, are showing promise in this pursuit.

NIR spectroscopy analyzes the composition of a human premolar tooth at Central Queensland University in Australia. Courtesy of Liza Pretorius/Central Queensland University.

NIR spectroscopy has been used in provenance (source) determination in a number of application areas.

Teeth are composed primarily of three mineralized tissues: enamel, dentine, and cementum. Enamel, the outermost layer, is the hardest substance in the human body, providing a protective shield for the softer underlying dentine and cementum. The primary mineral in both enamel and dentine is hydroxyapatite (HAp), a crystalline calcium phosphate with the chemical formula Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2. This mineral gives teeth their hardness and resilience, but it is susceptible to chemical changes that can lead to decay. Teeth also contain a small percentage of organic materials, mainly proteins, such as collagen and amelogenin, which contribute to the structural integrity of the teeth and play a role in their development. In addition, teeth are quite porous, holding up to 12% weight by weight water, with porosity increased following acid exposure and bacterial-induced decay.

An advantage of NIR spectroscopy compared with IR spectroscopy is the lower absorptivity of NIR wavelengths in mineralized tissue, and therefore a longer mean free path length (3.2 mm for photons at 7634 cm−1), allowing for the characterization of both the dentine and enamel components of the tooth1.

Given that tooth porosity, and thus water content, can be related to tooth defects, such as caries or acid-induced demineralization, imaging systems using one or two wavelengths associated with water bands are entering the market for clinical use.

Some of these existing systems designed to identify caries, tooth decay, and other structural damage include:

• The DIAGNOdent from KaVo Dental in Germany uses laser fluorescence at 655 nm to detect occlusal and interproximal caries, while SoproCARE by Acteon Group in France operates within the 440- to 680-nm range, using NIR and fluorescence to identify conditions such as caries, plaque, and inflammation.

• DEXIS CariVu from KaVo Kerr in the U.S. employs 780-nm NIR transillumination for real-time imaging to detect caries and cracks without x-rays. Similarly, SoproLIFE, also from Acteon Group, uses blue LEDs at 450 nm to excite dentin fluorescence for noninvasive decay detection.

• VistaCam iX HD from Dürr Dental in Germany combines visible and NIR (850 nm) imaging to visualize caries and plaque with high-definition images, providing a radiation-free alternative. The Canary System, developed by Quantum Dental Technologies in Canada, uses photothermal radiometry and luminescence at 655 nm to detect early decay and monitor cracks on various tooth surfaces, including around restorations.

• Finally, NIRQuest from Ocean Optics in the U.S. offers a spectrometer operating between 800 and 1600 nm, tailored for dental research to analyze enamel and other dental tissues nondestructively, facilitating the investigation of composition and the detection of anomalies.

NIR spectroscopic measuring equipment for chairside

quantitative assessment of tooth water content could be

developed, augmenting the current imaging technologies.

NIR spectroscopy has been used in provenance (source) determination in a number of application areas. For example, it was used to discriminate honey samples based on geographic source2, and it has been adopted in fisheries science as a tool for aging fish based on spectra of otoliths extracted from the fish ear3.

Given that tooth structure and chemistry can be influenced by the chemical environment of the mouth, the author explored the potential for NIR spectroscopy to characterize teeth based on factors such as tooth type, age, (animal) diet, place of origin, and sex (opening image)4.

Provenance determination

It is difficult for researchers to entirely rely on extracted human teeth samples, because they are often compromised due to decay and the presence of restorative materials. Therefore, for purposes of this study, bovine teeth were sourced from a local abattoir for experiments requiring large numbers of undecayed teeth (Figure 1). Bovine teeth share similar composition and characteristics with human teeth, making them suitable substitutes for experimental work5. And importantly, they are in ample supply in Rockhampton, Australia, which is known as the Beef Capital of Australia.

Figure 1. Liza Pretorius holding a bovine molar tooth (posterior tooth). Courtesy of Liza Pretorius/Central Queensland University.

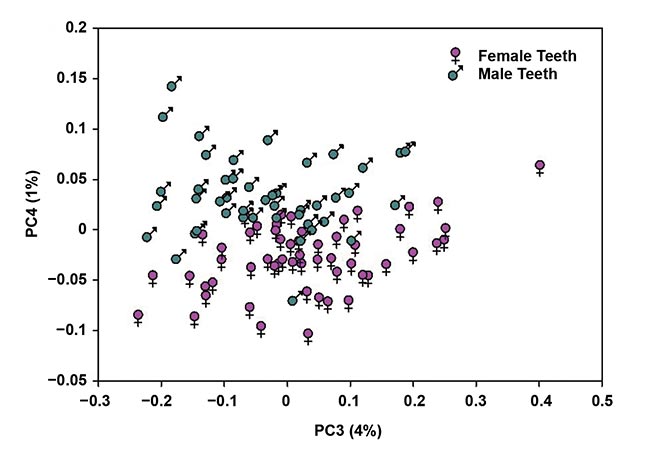

The results of the spectroscopic analysis were quite promising, as demonstrated by the principal component analysis (PCA) score plot, which shows adequate separation between male and female bovine teeth (Figure 2). The team is still researching what specific attributes were identified in the process that accounted for these differences.

Figure 2. A principal component analysis (PCA) score bi-plot based on NIR absorbance data for male and female bovine teeth (n = 101). The percentage of explained variation for each principal component is shown in brackets. Courtesy of Liza Pretorius/Central Queensland University.

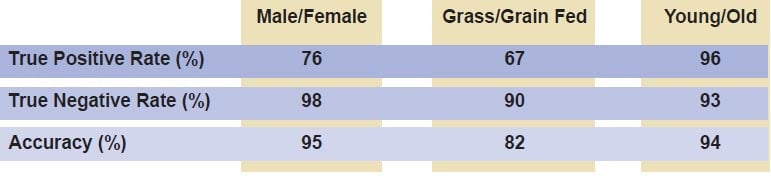

Discrimination results for sex, diet, and age for partial least squares-discriminant analysis models developed using absorbance data.

A combination of chemometric techniques, including support vector machines, partial least squares-discriminant analysis, artificial neural networks, and soft independent modeling of class analogy, were employed to develop models for classification of chemical properties based on sex, age, diet, tooth type, and place of origin. The table above shows results for a partial least squares-discriminant analysis model for the discrimination of teeth based on sex, age, and diet using NIR spectra in the wavenumber range 4000 to 10,000 cm–1, with prediction accuracy ranging between 82% and 95%.

Tooth water content

While current single or dual-NIR wavelength imaging techniques allow a qualitative assessment of tooth decay, quantitative monitoring of tooth water content, i.e., porosity, may be useful to provide more detail on a tooth’s clinical condition. Quantifying tooth water content would hold value in assessing the extent of tooth demineralization. This approach could facilitate precise determination of when to initiate treatment and allow for accurate prediction of treatment dosage requirements. In addition, since tooth moisture content generally decreases with age, this technology could potentially enhance age estimation methods6.

With this in mind, the research team at Central Queensland University developed a five-factor partial least squares regression model to predict tooth water content. The model achieved a cross-validation R² of 0.91 and a root mean square error of cross-validation of 0.4% w/w.

Applications of NIR spectroscopy

Further study revealed spectral differences between vital (meaning the nerves are intact) and non-vital teeth, which were attributed to the reduced organic content and increased porosity of non-vital teeth.

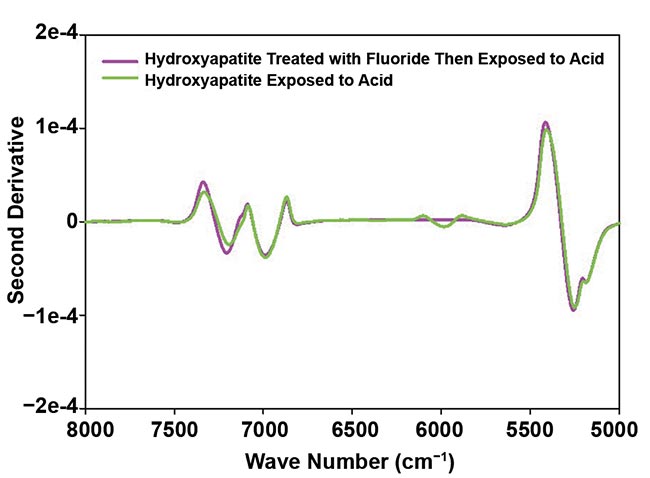

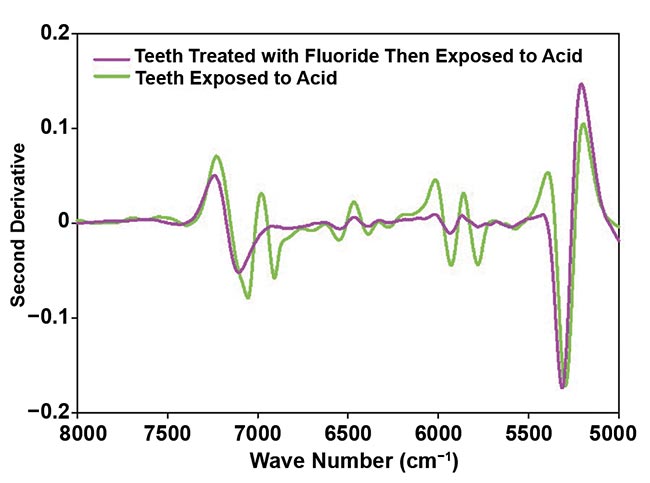

Figure 3 provides an example of findings in the context of the well-known protective influence of fluoride treatment against acid exposure. Acid-treated synthetic HAp and teeth showed spectral changes at ~6000 cm−1 and 6018 cm−1, respectively. These alterations result from the reaction of hydrogen ions in acidic conditions with hydroxyl groups in HAp, leading to water formation and partial breakdown of the HAp structure. Importantly, these changes were not observed in fluoride-treated samples, which is consistent with a protective effect of fluoride.

Figure 3. A second derivative of absorbance spectra of synthetic hydroxyapatite (HAp) treated with 22.6 mg/L fluoride and then exposed to an acid at pH 4.0 compared with HAp exposed to acid without a fluoride pretreatment (top); and second derivative of absorbance spectra of teeth treated with 22.6 mg/L fluoride and then exposed to an acid at pH 4.0 compared with teeth exposed to acid without a fluoride pretreatment (bottom). Courtesy of Liza Pretorius/Central Queensland University.

The significance of these findings lies in identifying the specific spectral range that can be used to quantify the extent of acid-induced damage to teeth. This information could guide clinical decisions and determine the appropriate treatment dosage, especially when hand-held devices become commercially available.

Further research

NIR spectroscopy could potentially be used in the

discrimination of samples based on distinct diets, grouping individuals by region.

The previously described work with bovine and human teeth hints at potential forensic or anthropological uses of NIR spectroscopy through classification of individuals based on sex, age, and diet. NIR spectroscopy could potentially be used in the discrimination of samples based on distinct diets, grouping individuals by region to minimize the need for more conclusive and costly tests, such as DNA analysis. Ongoing challenges will include developing a calibration model without access to known samples.

NIR spectroscopic measuring equipment for chairside quantitative assessment of tooth water content could be developed, augmenting the current imaging technologies. Tooth water content increases after acid exposure, and measurement of tooth water content could serve as an indicator of the overall health of the teeth. For example, the feature at 6018 cm−1, as shown in Figure 3, could quantify moisture content and be used in assessing tooth demineralization, guiding treatment decisions, such as fluoride dosage strength, and informing the timing of remineralizing and restorative procedures, thus individualizing treatment plans based on patients’ specific needs.

Meet the author

Liza Pretorius is the Principal Oral Health Therapist at Central Queensland Hospital and Health Services (CQHHS), in Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia. Her Ph.D. studies at Central Queensland University surround the investigation of dental tissue characterization using NIR spectroscopy and chemometrics; email: [email protected].

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Ryan Batley of Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Australia, for arranging procurement of bovine mandibles for use in this study, and JBS Rockhampton for the donation of mandibles. This research project is supported under the Commonwealth Government’s Research Training Program. The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by the Australian government.

References

1. R. Jones et al. (2003). Near-infrared transillumination at 1310-nm for the imaging of early dental decay. Opt Express, Vol. 11, No. 18, pp. 2259-2265.

2. T. Woodcock et al. (2007) Geographical classification of honey samples by near-infrared spectroscopy: a feasibility study. J Agric Food Chem, Vol. 55, No. 22, pp. 9128-9134.

3. I.M. Benson et al. (2023). The future of fish age estimation: deep machine learning coupled with Fourier transform near-infrared spectroscopy of otoliths. Can J Fish Aquat Sci, Vol. 80, No. 9, pp. 1482-1494.

4. O. Fejerskov and B. Nyvad, eds. (2015). Dental Caries: The Disease and Its Clinical Management. John Wiley & Sons.

5. G.H. Yassen et al. (2011). Bovine teeth as substitute for human teeth in dental research: a review of literature. J Oral Sci, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 273-282.

6. D. Arola and R.K. Reprogel. Effects of aging on the mechanical behavior of human dentin. Biomaterials, Vol. 26, No. 18, pp. 4051-4061.