Harsh Environments Will Define the Evolution and Future of Imaging Assemblies

By Greg Hollows

During the past three decades, constant and prolific increases in data transfer rates and processing speeds have transformed our daily lives — reshaping how we conduct business, diagnose disease, share information, solve problems, interact, and, fundamentally, how we live. This has cleared a path for significant improvements in cost-effective sensor technology, in the form of increased resolution, improved dynamic range, and higher sensitivity to increased spectrum use.

Currently, this shift is opening solution spaces for applications across industries. At the same time, it is guiding imaging forward into different environments. Optical assemblies such as imaging lenses must evolve to keep pace and take full advantage of these advancements — especially as imaging lenses enter new, harsh environments.

Imaging evolution

While favorable quality (and even supreme quality) imaging lenses have existed for a long time, as recently as two decades ago, a considerable percentage of the lenses used in industrial applications were developed in other industries, including security and photography. Manufacturers targeted the performance capabilities of these optics to the sensor and camera technologies of the time period. Generally, these lenses were envisioned to support indoor or in-lab use at resolutions of 0.3 MP. As it translated into application, users were very limited in both what they could see and the speed at which they could see it.

Athermal imaging lenses co-developed by Edmund Optics and Ruda Optical Inc. The solution maintains performance over a temperature range of −10 to 50 °C. Courtesy of Edmund Optics.

Since then, resolutions have skyrocketed, sensitivities have improved, and frame rates have increased dramatically. Package size and power consumption have significantly decreased as well, and the ability to see new parts of the spectrum has become possible. Moreover, all of these points of progress have been achieved at increasingly favorable and advantageous cost structures.

During the first decade in which these transformative changes were underway, developing lenses that could keep pace with the rapid increases in sensor resolution was the primary focus of the imaging industry. End users and systems integrators were the beneficiaries, because systems for factory automation and industrial inspection could be deployed to image increasingly small defects at measurement accuracies that transformed the manufacturing of everything from electronics to food and beverages to transportation.

More recently, the reduced package size and cost-effectiveness of sensor and camera technology are beginning to enable applications in spaces where imaging systems have historically struggled. Imaging systems are moving out of the lab and off the factory floor into an ever-expanding range of environments in which high performance is required under all circumstances, such as autonomous systems operating outdoors. Optical providers now must worry about more than just resolution; they need their products and solutions to survive and perform in extreme conditions.

Environmental considerations

Temperature fluctuations, moisture, dust, dirt, salt, frost, and oils are just some of the environmental concerns that lens designers must consider for lenses targeting new applications. In the past, agricultural applications of imaging, for example, most often pertained to the sorting of food for quality issues after harvesting. While these tasks were difficult and, in some cases, had to be carried out in the field, the environments in which these inspections occurred still offered a degree of control.

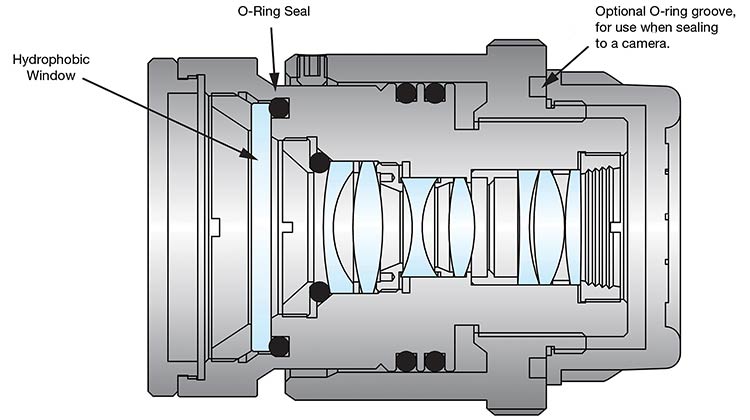

An ingress-protected ruggedized lens features an O-ring to seal out contaminants such as dust, dirt, and moisture, as well as a hydrophobic window at the front of the optical train. Courtesy of Edmund Optics.

Now, applications for viewing crops during growth, inspecting during fertilization, identifying and ablating weeds, and removing other unwanted vegetation are required to take place entirely in the field. This means that these applications are prone to potentially severe environmental conditions. Further, many imaging solutions are deployed on autonomous systems and are expected to be as compact as possible, have no (or few) moving parts, and deliver accurate functionality across a wide range of temperatures. This can be difficult due to thermal changes in the optics or if foreign materials end up on or inside the system.

Temperature

In addition to environmental considerations, lens designers today must deliver solutions that achieve great resolution to match sensor capabilities — which can require optical alignment to micron-level precision. At the same time, designers must ensure that lenses maintain optimal performance over a wide temperature range, where the materials in the lens can change size and position by microns. If not properly considered in the design stage, systems can lose focus over a temperature range, rendering them unusable for a time.

Designers can create products that compensate for temperature changes through the use of passive athermalization. In this design technique, changes in element spaces are considered during the design process, and the design is tailored accordingly to compensate to achieve balanced performance and focus at different temperatures. Predictably, this adds to the cost, complexity, and overall size of the design. It must therefore be considered at the start of the design process.

Stepping further into current design practices, the addition of specialized materials to the system, which enable the system to compensate for thermal shifts, can also be considered. This approach is most often used to further compensate for temperature swings in passively athermalized designs.

In the past, these techniques were mostly used for aerospace applications. They are now becoming a part of standard products and off-the-shelf designs.

Finally, designers may also use active athermalization. This approach involves the use of additional support hardware that may either “actively” compensate for or correct the focus of the lens system, or provide heating or cooling capability to maintain the lens system at a design focal length. Both of these examples require a form of feedback control for the active system to stabilize the optics at the desired system focus position or temperature set point, respectively.

Moisture and ingress protection

Many standard lenses are designed for use in reasonably clean environments. When exposed to harsher locations in a factory, an enclosure can be used for ingress protection against dust, water, and oils. Many emerging applications are moving toward environments in which imaging lenses will need to have this protection integrated directly into the lens.

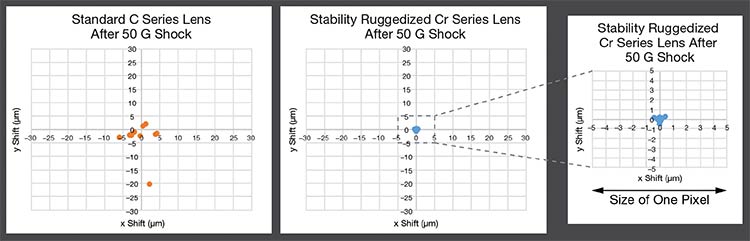

While the Edmund Optics standard, nonruggedized imaging lens (left) achieves strong performance, the pixel shift after 50 G of shock is more than a single pixel (center). Under the same amount of shock, the stability ruggedized lens (right) has <1-µm pixel shift — a much smaller value than the size of a pixel. Courtesy of Edmund Optics.

When sealing a lens against harsh environments, the mechanical designs and adhesives manufacturers use raise numerous considerations of their own. From a mechanical perspective, many of the lens ergonomics must be changed and reduced to diminish opportunities for particulates to enter the lens housing. Removing a variable iris and replacing it with a fixed aperture, and then eliminating ergonomic focus mechanisms for a simplified, multi-rotation focus system, are among the trade-offs designers must make.

Additionally, the use of less desirable optical adhesives is needed to ensure complete sealing at points of contact between glass and metal to prevent potential ingress. These adhesives are often more difficult to work with, require special handling, and may have extended cure times. The thermal range accommodations (outlined above) must be considered, too, or lenses can separate from the housing, affecting both image fidelity and ingress protection.

Shake, rattle, and roll

Many applications that are required to take place in harsh environments experience shock and vibration issues. These can reduce the performance and usable lifetime of the lens. Consider the application of field-deployed medical diagnostic equipment. Many of these devices are designed to be component parts of mobile labs. They must therefore survive regular transport — not always on ideal road conditions and field use. And they must produce near-clinical lab reliability.

Optomechanical design considerations are strenuous, serving to ensure that both high levels of optical resolution and system alignment are maintained, since shocks and vibrations can wreak havoc on optical tolerances and take calibrated systems out of optic-sensor alignment. To perform in these harsh environments, the optics that comprise these designs must be glued firmly in place to prevent movement or disruptions from constant shocks and vibrations. These lenses will additionally have simplified mechanical focus systems that will not allow for metal-to-metal misalignment, which can occur in more ergonomic focus mechanisms used in standard lenses.

Future evolution of imaging assemblies

Processing speeds will continue to advance, enabling sustained improvements in sensor technology in the future. This will in turn expand the number of applications where imaging can change the ways in which our world functions. The opportunity to perform more remote sensing, improve medical diagnostics both closer to home and in the field, enhance mobility and vehicle safety, and increase food production while reducing waste will contribute to a better, more cost-effective quality of life.

For imaging lenses, evolution was paramount — a necessary step to ultimately improving their performance. This performance is now arriving in the field, where it is facing the associated environmental challenges and problems with survivability.

The next challenges will be associated with visualizing expanded portions of the spectrum — both individual sections and multiple parts fused together. These advancements must also achieve a reduced size compared to existing imaging systems and without compromising — and perhaps even improving — optical performance. Advancements in computational imaging and machine learning/AI will also open opportunities. These, too, will place new demands on imaging systems, challenging future engineers to conceptualize even more sophisticated imaging assemblies and systems.

Published: September 2025