Fluorescence Microscopy and Microfluidics Intersect for Biological Discovery

A combined platform allows automated, wide-field analysis of neuronal activity and dynamic processes.

By Enrico Lanza, Valeria Lucente, and Ilaria Cavallo

Microfluidics has transformed from a niche technology into a fundamental tool for biological experimentation during the last decade. When coupled with wide-field fluorescence microscopy, it enables the observation of biological systems at both the cellular and population levels, and at the same time offers precise control over experimental conditions. Yet despite its potential, microfluidics remains underutilized in certain areas of research, primarily due to the complexity of integrating disparate components such as pumps, incubators, and imaging systems, each with its own control software and protocols.

Accurate measurement and sample identification have brought together microfluidics and fluorescence microscopy. Courtesy of iStock.com/Love Employee.

This complexity translates into limited adoption of the technique and associated automation in live-cell imaging and microenvironmental control, which are crucial to observing dynamic biological responses. To address these challenges, a fully integrated platform has been developed that unites high-resolution, wide-field fluorescence imaging, programmable microfluidics, and environmental parameter regulation in a single, user-friendly system. This approach not only makes automated experimentation accessible to researchers with limited expertise in microfluidics or programming but also enables entirely new classes of experiments — real-time behavioral quantification, parallel stimulation of organoids, and high-throughput functional imaging on a single device.

From fragmentation to integration

Setting up a conventional fluorescence microscope connected to a microfluidic system, which requires precision pumps and an incubator to maintain the sample, can be both troublesome and expensive. This is due to the complex and time-consuming process of integrating various components from separate sources, ensuring they work together seamlessly while maintaining the necessary environmental conditions for the sample. Moreover, the costs associated with purchasing specialized equipment (such as microfluidic pumps, incubators, and high-end cameras) can be prohibitive for many research groups. Additionally, the technical expertise required to operate and maintain such a system can be challenging for researchers without extensive experience in both microscopy and microfluidics. This can lead to delays in experimentation, as well as potential issues with data accuracy and reliability.

Precision flow matters

Before even beginning a microfluidic experiment, one of the most crucial (and often underestimated) decisions is how to deliver fluids through the device. Choosing an inappropriate flow system can compromise the entire experimental outcome. In microfluidics, flow rate directly affects shear stress on cultured cells, influencing their proliferation, spatial organization, and protein secretion. For sensitive biological systems, even small variations can lead to significant changes in phenotype or function.

With integrated microfluidic pumps and a large field of view paired with high resolution, iFLUOR is an innovative platform for life sciences studies. Courtesy of D-Tails srl SB.

Reliable and precise control of flow is therefore essential. Current solutions include pressure-driven systems (such as compressed bottles), peristaltic pumps, and syringe pumps. Among these, syringe pumps are increasingly recognized as the gold standard for high-precision microfluidic experiments. Compared to pressure-driven systems, syringe pumps offer several advantages:

• Superior flow stability, eliminating the pulsation common in peristaltic pumps, which can disrupt delicate biological assays.

• Higher pressure capability, enabling the use of more complex or high-resistance microfluidic designs.

• Accurate volume delivery, crucial for experiments involving the timed administration of drugs or stimuli at microliter or nanoliter scales.

The possibility of using four different integrated syringe pumps — each independently controlled and programmable through the same unified interface as the microscope and incubator — ensures that even nonexpert users can apply optimal flow conditions without compromising the biological integrity of the experiment. The pumps in an integrated system support programmable infuse and withdraw modes, are compatible with syringes up to 10 ml, and allow flow rates ranging from 1 µl to 1 ml per minute. Furthermore, the four programmable syringe pumps enable up to three days of continuous operation, minimizing the need for user intervention and making long-term time-lapse experiments more practical and reliable.

To improve performance and experimental consistency, the integrated system includes a preheating module capable of heating injected fluids up to 40 °C, ensuring that thermal conditions remain stable from the reservoir to the microfluidic chip. A built-in leakage control system with sensors continuously monitors the integrity of fluid pathways and automatically halts the experiment if a leak is detected, preventing contamination of the fluid and preserving the integrity of a delicate biological sample.

All these functionalities are managed through a single, intuitive software interface that centralizes the control of pumps, temperature, and environmental parameters. This simplifies the workflow and significantly lowers the learning curve, enabling researchers to conduct complex, multiday experiments with minimal oversight while being promptly alerted in case of technical issues.

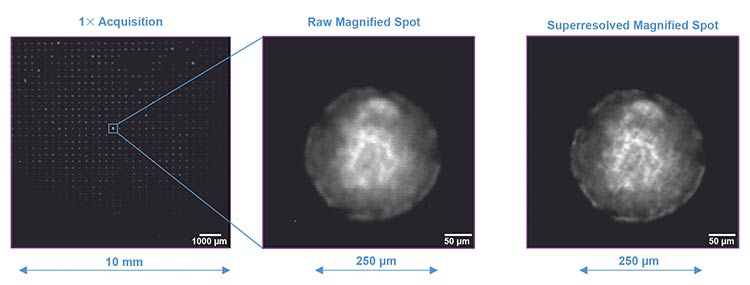

(From left) Full field of view with neurosettes, detail of a single neurosette, and a single neurosette enhanced with an electronic zoom

algorithm. Courtesy of Marco Leonetti and Lorenza Mautone from Center for Life Nano- and Neuro-Science, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia.

From detail to throughput

Fluorescence microscopy, a technique that uses fluorescent probes to visualize cellular structures and functions, has long been a cornerstone of molecular biology. While much of the early innovation in this field was directed toward improving spatial resolution, enabling the visualization of increasingly finer subcellular structures, a major shift is currently taking place in life sciences research. The technique’s uses are now expanding toward high-throughput screening and parallel analysis of multiple biological samples. This transformation is driven by the growing demands of fields such as drug discovery, systems biology, and personalized medicine, where the ability to compare responses across a large number of biological replicates or experimental conditions in a single acquisition is crucial. This evolution is also aligning the technique with the utility of microfluidics.

Supporting this shift in fluorescence microscopy, modern CMOS sensors have evolved to combine high spatial resolution with fast acquisition speeds and low noise, making them ideal for integration into systems that support wide-field fluorescence imaging. For example, sensors such as the Sony IMX541 offer a 20.2-MP resolution and, when used with slightly magnifying optical configurations, provide an effective pixel size of 2.5 μm. The use of a global shutter ensures all pixels are exposed simultaneously, eliminating motion artifacts during rapid image acquisition.

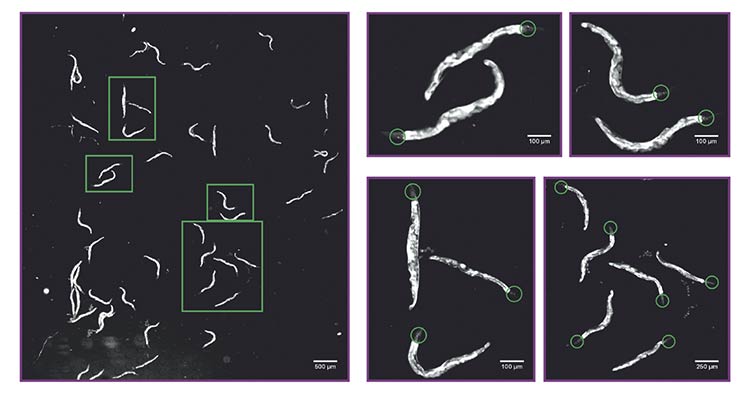

Calcium imaging of a population of Caenorhabditis elegans expressing a calcium indicator in amphid wing “C” (AWC) chemosensory neurons. The system allows the recording of the activity of multiple nematodes (roundworms) at once (50 in the left image), enabling identification of tiny details such as somas and neurites of neurons with calcium indicator expression (panels on the right, green circles). Courtesy of D-Tails srl SB.

These sensors also achieve excellent signal fidelity even at low light levels — avoiding photodamage — due to a quantum efficiency of 65.9%, low dark noise (~2.1 e?), and a dynamic range of >70 dB. With frame rates up to 18 fps at full frame, they are well suited for both high-throughput screening and long-term time-lapse imaging.

Paired with a relay lens optical

configuration, CMOS-based systems can achieve fields of view of up to

10 mm × 10 mm. This setup is particularly advantageous for monitoring multiple biological samples in parallel — such as entire populations of Caenorhabditis elegans or arrays of beating cardiomyocytes — within a single acquisition. Advanced configurations further enhance image quality through super-sampling techniques — such as piezo-controlled mirror scanning (where piezoelectric actuators precisely move mirrors) — and by replacing the relay lens with a classical microscope objective and tube lens assembly. This setup can push resolution down to 0.7 μm across the same large field of view.

Examples in the life sciences

This powerful combination of large field of view and high resolution is not just a technical achievement: It has direct implications for biological research. For instance, in neurodevelopmental studies, D-Tails Research tested an imaging system that combines microfluidics and fluorescence microscopy on Neurosetta plates, designed to model early brain development, which feature gold-coated, micropatterned substrates that induce the formation of up to 900 brain rosettes. Each microenvironment is ~250 μm in diameter, and the ability to image the entire well at once allows for rapid and consistent phenotypic assessment. With the enhanced resolution mode, individual rosette structures can be resolved and analyzed in detail, highlighting both macroscopic patterning and subcellular features.

The platform has also proved to be effective in studying neuronal activity using genetically encoded calcium indicators in C. elegans. In this application, ~50 nematodes (roundworms) were loaded into a specially designed microfluidic chip compatible with fluorescence imaging. The system’s large field of view and fine resolution enabled simultaneous monitoring of neuronal activity in all animals while exposing them to controlled flow perturbations. The imaging system could resolve fine structures such as the amphid wing “C” (AWC) sensory neuron soma (6 to 8 μm) and neurites (~2 μm), providing the detail necessary to correlate structural and functional dynamics across populations.

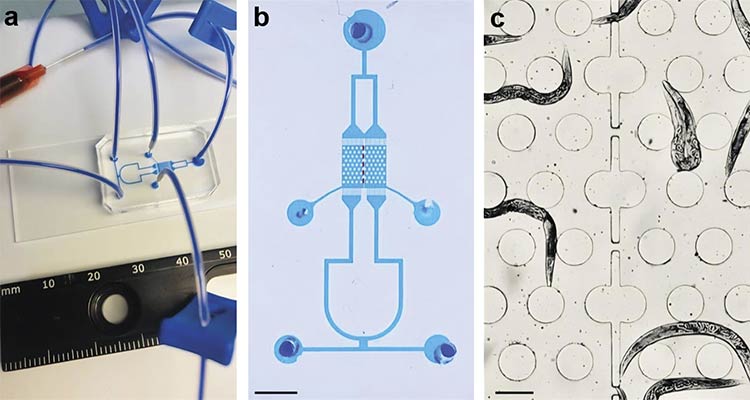

The microfluidic arena for high-throughput Caenorhabditis elegans calcium imaging

experiments with multiple-strain confinement. A photo of the proposed microfluidic chip filled with xylene cyanol tracking dye (a). A higher-magnification image of the chip with dotted lines marking the interface between the two chambers (b) (scale bar = 3 mm).

A bright-field image of the chip showing the worm barrier region separating two strains of C. elegans (c) (scale bar = 200 µm). Courtesy of D-Tails srl SB.

Importantly, due to the expanded field of view, it was possible to collect data from a statistically relevant number of animals in a single imaging run. Previous systems, with their limited field sizes, required multiple separate acquisitions to gather equivalent sample sizes. This improvement increases throughput and experimental robustness without the need for multiple imaging sessions.

To further improve experimental throughput and enable comparative studies, a custom-designed microfluidic chip was developed to simultaneously confine and image two distinct C. elegans strains under identical flow conditions. The 3- × 3-sq-mm recording area is partitioned into two chambers separated by worm barriers that enable fluid exchange while preventing intermixing. Each chamber features a hexagonal array of micropillars (200 μm in diameter and spaced 100 μm apart) that support natural worm locomotion. Independent loading channels and multiple inlets allow for selective chemical stimulation, making the platform ideal for parallel analysis of control and mutant strains within the same imaging session.

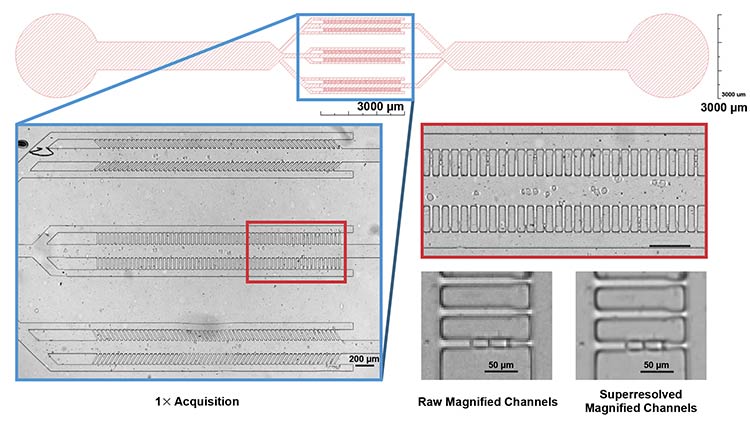

The design of the microfluidic system. In the blue box (top), channels for trapping cells are shown. The iFLUOR system enables high-resolution 1:1 imaging of the channels (left). This resolution preserves a high level of detail even after magnification of the native image (red box, right). A superresolution algorithm further enhances image sharpness, as shown in the zoomed image of a single channel with two cells before and after superresolution algorithm application (bottom right). Courtesy of Simone Scalise and Mattia Miotto/Center for Life Nano- and Neuro-Science, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia.

Such an integrated platform has also been applied to cancer research using “Mother Machine” devices — microfluidic chips designed to isolate single cancer cells in narrow (15 μm wide) trapping channels. Human leukemia cells (Jurkat T-cells) were loaded into the chip and monitored over 72 h with image acquisitions every 3 min. The wide field of view allowed simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of cells, while the system’s native resolution, combined with digital post-processing magnification, facilitated clear identification of cell-division events. More advanced configurations of the integrated system can include custom image-processing algorithms to enhance pixel resolution down to ~0.685 μm, providing even more precise visualization and enabling detailed monitoring of cell size dynamics. This approach demonstrates the capability to deliver consistent imaging analysis for both broad- and fine-scale observations.

These examples illustrate how integrating advanced optics, wide-field CMOS sensors, and programmable microfluidic control can transform fluorescence microscopy into a truly high-throughput, automation-friendly tool. Rather than being limited to static snapshots or manual region-of-interest selection, researchers can now perform dynamic, quantitative studies across entire populations or chip arrays — paving the way for faster and more reliable biological insights.

Meet the authors

Enrico Lanza, Ph.D., is the software lead at D-Tails srl in Rome. He earned his doctorate in life sciences from Sapienza University of Rome, with a background in physics of complex systems. He develops imaging and analysis platforms for neuroscience and biosensing, integrating experimental design, microfluidics, optical imaging, and advanced image processing. He collaborates with Sapienza University, the Italian Institute of Technology, and the Italian National Institute of Health; email: lanza@d-tails.com.

Valeria Lucente is a laboratory technician at D-Tails Research and a biology student at Sapienza University of Rome. Since 2021, she has worked at the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT) as part of the Cancer Detection project, gaining experience in molecular biology, soft lithography, and calcium imaging, using yeast and Caenorhabditis elegans as model organisms. She is currently focused on exploring the biological applications of iFLUOR technology, contributing multidisciplinary expertise to support innovative research; email: lucente@d-tails.com.

Ilaria F. Cavallo holds a master’s degree in biology and cellular technologies from Sapienza University of Rome. She has worked on cancer detection projects within the joint lab between D-Tails Research and the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT). She has also conducted chemotaxis assays with urine samples from breast cancer patients and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and has studied G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) mutants for ligand identification. Currently, she is working on iFLUOR technology; email: cavallo@d-tails.com.

/Buyers-Guide/D-Tails-srl-SB/c34227