Chasing the Wind: Ultrafast Spectroscopy Captures Nature’s Fastest Processes

Ultrafast spectroscopy systems continue to become more compact without any compromise to integration, automation, and accessibility.

By Greta Bucyte, Gabriele Stankunaite, and Mikas Vengris

Although ultrafast laser sources are integral to

today’s spectroscopy system designs and applications, the field of spectroscopy predates the invention of lasers. As early as 1940, researchers began to examine photochemical reactions on the microsecond timescale. Molecules in various solutions were excited, or even split, by brief flashes from xenon discharge lamps, resulting in changes in the absorption spectrum of the solution.

Courtesy of Light Conversion.

These observations were some of the first short-lived radical reactions — discoveries that ultimately earned Ronald G.W. Norrish and George Porter the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1967. The acclaimed method, termed flash photolysis, remains in use for nano- and microsecond absorption experiments.

While early experiments, such as those from the Nobel laureates, relied on light flashes that split the molecules, laser pulses in modern systems merely excite them to track spectral changes. With the advent of lasers, scientists quickly learned to shorten the light flashes to nano-, pico-, and eventually femtosecond durations. By the early 1980s, picosecond spectroscopy had gained traction, with optical parametric amplifiers (OPAs) used to align laser wavelengths with experimental needs. Dye lasers initially dominated as tunable sources, enabling the generation of the first femtosecond pulses and broadband radiation.

The application of Kerr lens mode locking in gain media led to the subsequent rise of solid-state Ti:sapphire lasers in the market for wavelength-tunable sources1. This technological shift propelled spectroscopy experiments into the femtosecond domain, enabling the exploration of ultrafast processes that are relevant to materials science, biology, and chemistry. It became evident that nature is full of light-induced processes that operate on these incredibly short timescales: Charge relaxation in crystalline and amorphous materials, molecular vibrations, and photosynthesis all occur in mere femtoseconds.

The need to examine such rapid processes spurred the development of equipment capable of generating femtosecond pulses. Early manufacturers, such as Spectra-Physics, Coherent, Clark-MXR, and Quantronix, pioneered femtosecond laser sources. In parallel, groups including Light Conversion advanced innovation in ultrafast OPAs. The popularity of ultrafast spectroscopy using solid-state femtosecond laser sources and OPAs surged after Ahmed Zewail earned the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1999 for his research in femtosecond spectroscopy.

A helpful analogy to better understand ultrafast spectroscopy is to think of this process as photography with short exposure times. Cameras with fast shutters capture athletes in lightning-fast motion, making them appear “frozen” in time.

In the same manner, femtosecond lasers enable researchers to observe rapid

molecular events on vastly shorter time-scales, ranging from micro- to femtoseconds. These timescales are necessary to track essential light-induced processes in real time, such as molecule excitation, ionization, energy and/or charge migration, and regrouping as they leave distinct spectroscopic traces that function as signatures. Decades after its emergence as a core application for the technology, the study of photosynthesis remains among the most fascinating uses of ultrafast spectroscopy.

Photosynthetic absorption occurs in femtoseconds, after which pigments

— carotenoids and chlorophylls — enter an excited state. Femtosecond spectroscopy enables scientists to observe each stage of this intricate process. By mapping the evolution of absorption and fluorescence in individual pigments over incredibly short time frames, researchers

gained a deeper understanding of the complex chemical steps that convert light into energy-rich organic carbohydrates and oxygen.

Research into photosynthesis delves into foundational processes of life. It also stimulates the development of technologies, such as artificial photosynthesis, which is paving the way for sustainable energy solutions.

Ultrafast spectroscopy also drives advancements across various industries. By uncovering the intricate behaviors of materials, it contributes to the development of industrial technologies, offering insights into processes occurring on pico- to femtosecond timescales. In OLEDs, for example, ultrafast spectroscopy provides a detailed understanding of exciton dynamics, revealing how excitons are generated, migrate, and decay. It helps to identify the timescales of recombination and energy transfer to optimize these sources. For solar cells, ultrafast spectroscopy plays a key role in addressing energy loss pathways2. It also detects trap states and defects that capture charge carriers, guiding the design of materials to minimize these efficiency losses, giving ultrafast spectroscopy utility in processes to enable semiconductor industry applications.

Exploring molecular dynamics

From photochemical reactions to energy transfer processes, ultrafast spectroscopy offers a powerful arsenal of techniques for unraveling the mechanisms underlying a wide array of phenomena. Many can be used to observe molecular processes and provide benefits that are unique to each method.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy techniques, such as time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC),

fluorescence upconversion, and optical Kerr shutter, provide insights into the excited-state dynamics of molecules. TCSPC measures fluorescence and

phosphorescence lifetimes, which correspond to the time that molecules spend

in their excited states before returning

to the ground state. These lifetimes

reveal information about molecular

environments, energy transfer processes, and interactions with surrounding

molecules. However, the fastest events that TCSPC can capture are limited to tens of picoseconds due to detector response time.

Fluorescence upconversion achieves femtosecond resolution in tracking fluorescence decay using nonlinear optics. This enables researchers to observe rapid energy dissipation and relaxation processes that occur within molecules on timescales as short as a few tens of femtoseconds.

Kerr gating, meanwhile, simplifies the process of capturing the full spectra of emitted fluorescence without wavelength scanning. This can be a time-consuming task with wavelength scanning, because it is less efficient in capturing fast dynamic processes.

In fluorescence techniques, the detected light must be radiated by the sample;

observations are inherently limited to emissive excited states, neglecting

non-emissive states and ground-state

processes. Time-resolved transient

absorption spectroscopy addresses

this limitation by capturing transient intermediates in both ground and excited states.

Using two ultrashort laser pulses,

time-resolved transient absorption spectroscopy provides snapshots of molecular evolution, revealing vital processes that cannot be detected via fluorescence.

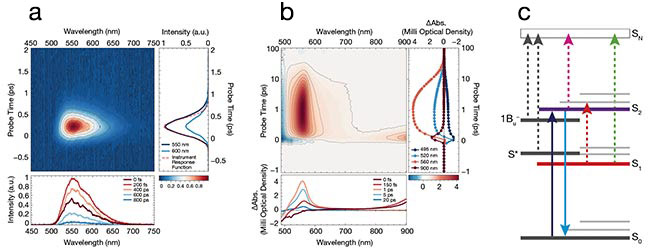

For example, in β-carotene, a naturally occurring pigment known for its photoprotective properties, Kerr gating fluorescence spectroscopy enables the observation of only the fluorescence decay from the second singlet excited state in the molecule to the ground state (S2 → S0) (Figure 1a). However, transient absorption spectroscopy reveals additional processes, such as excited-state reabsorption and

the involvement of non-emissive states such as the first singlet excited state (S1), or the “dark state,” and intermediate species in energy transfer and photoprotection (Figure 1b). The comprehensive nature of this approach enhances the understanding of complex molecular behaviors by providing a more complete picture of dynamics across all relevant states.

Figure 1. Kerr gate measurements in ß-carotene showcase the resolution of the measurement (a). The second singlet excited state in the molecule to the ground state (S2 → S0) fluorescence of carotenoids is ultrafast (100 fs). Therefore, the measured data is instrument response function-limited. Spectral dynamics of ß-carotene in solution acquired using a transient absorption spectroscopy system (b). Energy states of ß-carotene (c). The first singlet excited state (S1) is referred to as a dark state because it does not emit fluorescence. Yet it plays a crucial role in energy dissipation and photoprotective mechanisms. Courtesy of Light Conversion.

The significance of multiple timescales

Transient absorption measurements capture the earliest dynamics on the ultrafast timescale, such as vibrational relaxation and intersystem crossing of electronically excited molecules. These processes occur almost immediately after excitation and define the initial distribution of energy within the system.

Monitoring these ultrafast events

can provide a foundational understanding of how energy is directed or dissipated before slower processes take over. However, this does not mean that the later-occurring events are less important for delivering

essential information. After all, the real-life consequences of ultrafast events — such as sugar production in photosynthesis — manifest long after the process has consumed the initial photon energy.

To follow the dynamic initiated by ultrafast events, time-resolved methods must also cover timescales extending from nano- and microseconds all the

way to seconds. Therefore, understanding long-lived states such as triplet-

state formation, charge separation, and recombination, which are the products

of photochemical reactions, is as important as accessing initial femtosecond dynamics. In fact, it is at these times

that one can evaluate the stability and efficiency of molecular systems and

materials. Molecules with extended excited-state lifetimes require careful investigation using nanosecond delays to fully characterize their nonradiative decay pathways and other significant dynamics. In this context, flash photolysis — or nano- to millisecond transient absorption — remains as useful today as when it was first conceived in the last century.

The principle of flash photolysis is analogous to the femtosecond transient absorption experiment but it operates with delays in the nano- to microsecond range. In femtosecond transient absorption, moving a mechanical delay stage — which increases the distance that the light must travel to reach the sample — adjusts for

the delay between pump and probe pulses. The delayed probe pulse is obtained

from an electronically triggered external probe laser. A practical example of

studying dynamics across different

timescales is the measurement of a colored glass filter designed to transmit

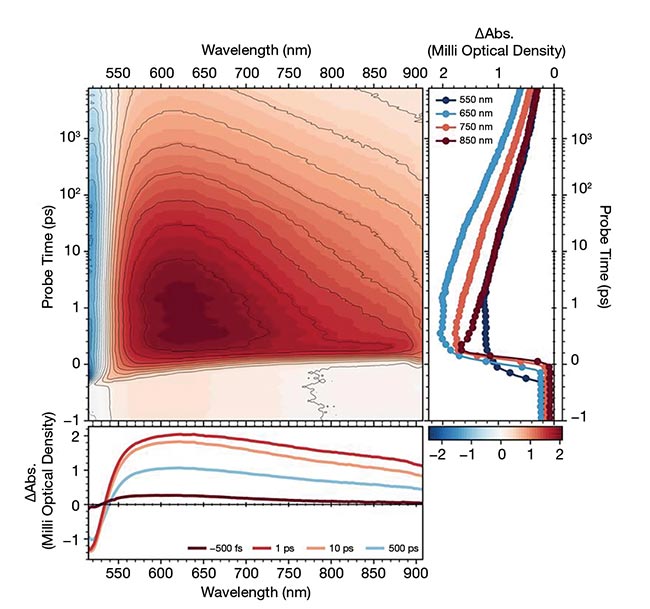

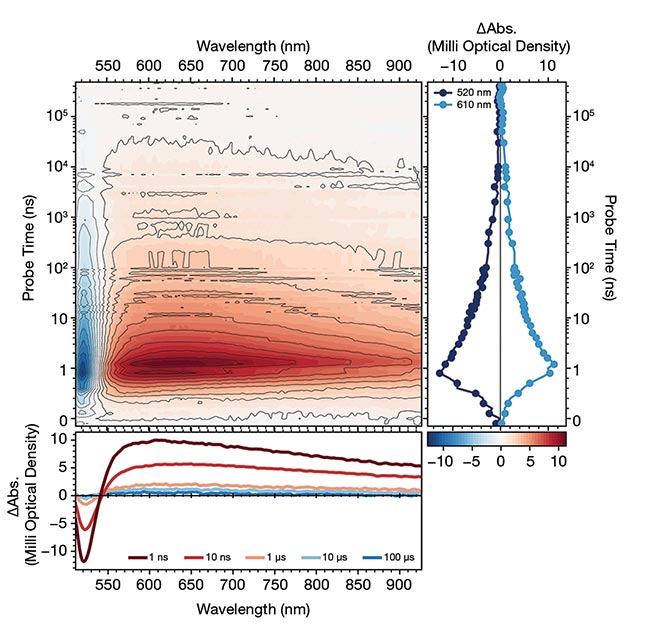

light >530 nm, enabling the tracking of kinetics from pico- to nanoseconds (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pump-probe dynamics of a colored glass filter designed to transmit light >530 nm. Ultrafast dynamics in the femtosecond regime, acquired via transient absorption spectroscopy using a Light Conversion HARPIA-TA instrument (top). Longer-lived dynamics on the nanosecond timescale, measured with the instrument’s flash-photolysis module (bottom). Courtesy of Light Conversion.

Having a broad time window that spans pico- to nanoseconds is essential to construct a comprehensive kinetic picture of a system. In photochemistry, for example, such a broad window enables researchers to study ultrafast bond cleavage and slower product formation. By following through the entire temporal evolution from initial excitation to the final product of the captured photon, researchers can reconstruct the full dynamic sequence and avoid incomplete or incorrect conclusions.

Laser parameters define performance

Modern low-maintenance lasers free up valuable time and effort, allowing researchers to focus on their experiments and industrial end users to complete their tasks. Different laser types excel in various applications and spectral regions,

and certain applications require multiple

lasers for comprehensive studies.

Researchers and system end users must carefully select the most suitable laser based on factors such as power, tunability, bandwidth, size, and cost. Modern-day solid-state femtosecond lasers, operating at high repetition rates, combine multi-millijoule pulse energy and high output stability, making them ideal light sources for scientific research. Additionally, they

can be equipped with OPAs, offering a broad tuning range from the deep-ultraviolet to the mid-infrared to meet specific measurement needs for numerous applications.

Tunability is a fundamental requirement in modern spectroscopy, because it enables a wealth of experimental

possibilities and new use cases as a result. The precise adjustment of the wavelength of the light source is key to spectroscopic versatility, allowing users to selectively excite specific energy levels within molecules and materials, enable powerful nonlinear spectroscopic techniques,

conduct time-resolved studies, and characterize materials with wavelength-dependent properties.

Traditional lasers offer some degree

of tunability, but they are often limited in their spectral range. To overcome these limitations, users in R&D environments frequently turn to systems that combine lasers with OPAs. This powerful pairing ensures high-intensity, highly tunable, and coherent light sources.

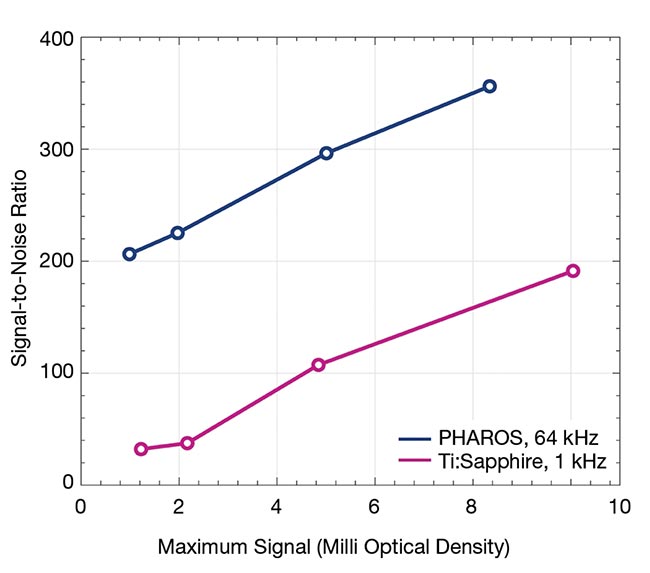

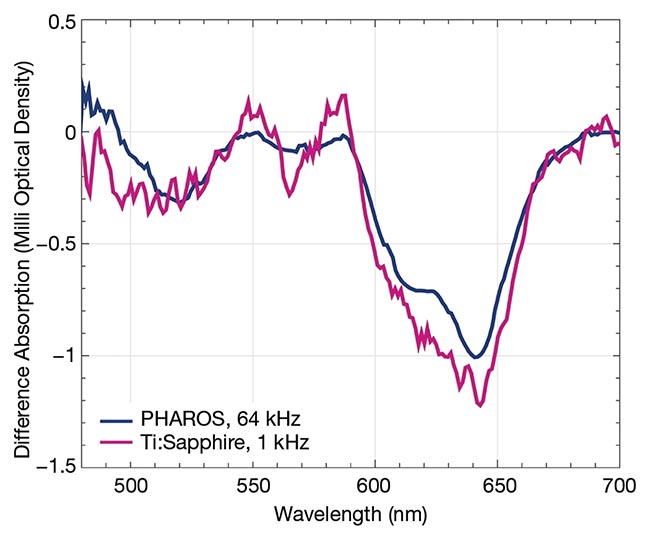

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is another critical factor in obtaining high-quality spectroscopic measurements. Ytterbium-based lasers, known for their high repetition rates, achieve excellent SNR even with low-pulse energies (Figure 3). Ideally, scientists and users in research settings aim to illuminate samples under natural conditions, but ultrafast spectroscopy demands femtosecond pulses to

capture molecular phenomena occurring

on these ultrafast timescales. High repetition rates play a crucial role in this process. Rather than relying on a few high-energy pulses, users can accumulate a sufficient signal by using many low-energy pulses to enable precise and

meaningful analysis of ultrafast dynamics.

Figure 3. The measured difference absorption spectra of cadmium selenide/zinc sulfide quantum dots using low- and high-repetition-rate lasers with 5-s acquisition time (top). Best-effort signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs), achieved via transient absorption spectroscopy driven by a Ti:sapphire laser at 1 kHz and a femtosecond laser at 64 kHz (bottom). Courtesy of Light Conversion.

In fields such as biophysics, physical chemistry, photovoltaics, and semiconductor physics, a white light continuum (WLC) is often deployed as a probe source in femtosecond pump-probe

experiments. These experiments require two laser pulses: The first excites the sample and the second arrives with a controlled delay to measure changes in transmittance caused by the excitation. Use of a WLC is particularly attractive as a probe source due to its broad multi-octave spectral range, which enables

the study of multiple transitions within the investigated material. The sensitivity of these measurements depends on the number of photons in the probe pulse. Since the number of WLC photons

detected per second scales linearly with the repetition rate, its increase significantly enhances the experiment’s SNR. This reduces noise and improves measurement precision.

Toward single-box spectroscopy

Spectroscopy systems’ remarkable transformation is marked by an evolution from complex, multicomponent setups to integrated, single-box solutions. This shift has created several key advantages, including enhanced ease-of-use, improved stability and reliability, and reduced maintenance requirements.

These advancements have increased

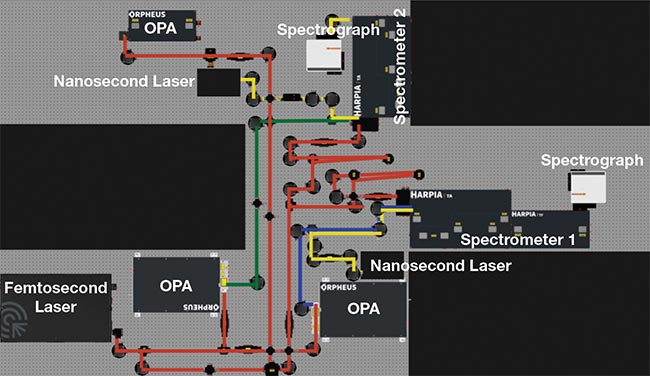

the convenience and efficiency of spectroscopy while empowering researchers across diverse scientific fields by simplifying the access to powerful analytical techniques. Today, advanced spectroscopy setups may integrate a single laser with multiple OPAs, allowing researchers to perform a variety of operations within a single, cohesive system. Housing multiple functionalities in one system marks a significant step forward in efficiency and flexibility (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A dual-spectrometer system deployed at the University of Cambridge. The system, capable of performing transient absorption (TA) and reflection in bulk, microscopy, and flash photolysis experiments, was designed and manufactured by Light Conversion and supplied by Photonic Solutions. It also features a time-resolved fluorescence (TF) module, three optical parametric amplifiers (OPAs), two nanosecond-pulsed lasers, a femtosecond-pulsed laser, and two spectrographs. Courtesy of Light Conversion.

Driven by the goal of making spectroscopy

more accessible, the industry continues

to innovate as it moves toward more

compact, single-box transient absorption

systems. This dynamic — shrinking

systems and growing capabilities —

signals that the future promises even

greater advancements in integration,

automation, and accessibility.

Meet the authors

Greta Bucyte is a product manager for

spectroscopy systems at Light Conversion;

email; greta.bucyte@lightcon.com.

Gabriele Stankunaite is head of marketing

and communications at Light Conversion;

email: gabriele.stankunaite@lightcon.com.

Mikas Vengris is a professor at the Laser

Research Center, Faculty of Physics, Vilnius

University, and an R&D engineer at Light

Conversion. His research focuses on ultrafast

laser applications for investigating dynamic

processes in various materials; email: mikas.vengris@lightcon.com.

References

1. R. Jimenez and G.R. Fleming. (1996).

Ultrafast Spectroscopy of Photosynthetic

Systems. Biophysical Techniques in

Photosynthesis, J. Amesz and A.J. Hoff, eds.

Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration,

Vol. 3, Springer, Dordrecht.

2. S. Srivastava et al. (2023). Advanced

spectroscopic techniques for characterizing

defects in perovskite solar cells. Commun

Mater, Vol. 4, No. 52.

/Buyers-Guide/Light-Conversion/c16417