Full company details

VIGO Photonics

Poznanska 129/133

Poznanska 129/133

05-850 Ozarow Mazowiecki

Poland

Laser-based spectroscopy finds diagnostic answers in breath

BioPhotonics

Jul/Aug 2025Highly sensitive detectors and measurement techniques have been integrated into sensor systems, identifying substances linked to a variety of medical conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, and cancer.Jedrzej Mijas, VIGO Photonics

Breath analysis has emerged as a promising noninvasive diagnostic tool for detecting a wide range of diseases by identifying biomarkers in exhaled gases. And advanced optoelectronic systems, particularly those based on mid-infrared (MIR) laser absorption spectroscopy, have been employed to identify these biomarkers. This technology has shown great promise for in vivo glucose sensing and early detection of dental decay.

Infrared sensing can be used to monitor laser dental therapies. Courtesy of VIGO Photonics.

Human breath consists of >3000 trace substances, whose elevated concentrations can indicate health conditions.

The field of laser gas analyzers has seen rigorous development in recent years. Due to the nature of the light sources used, a single laser can target only one absorption peak — and therefore only one molecule — of interest. MIR wavelength lasers, between 3 and 8 µm, garner special interest because the absorption features of the various gases are more distinctly separated than in the near-infrared, between 0.76 and 1 µm, and shortwave infrared, between 1 and 3 µm.

Sensing capability expands

IR sensing is a technology that has been used for decades in industrial and security applications, but system design around this regime has only recently matured enough to be employed in a variety of medical settings to exploit the unique possibilities in this part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Advancements in the development of optical components and signal processing capabilities and the two most important ingredients for an IR system — a light source and a detector — have contributed to the widespread medical use of these devices. Certain versions are undergoing clinical trials for potential placement in hospitals and medical offices.

Most IR systems have already benefited from the enormous progress in IR laser technology, namely those suited for MIR wavelengths, such as interband cascade lasers (ICLs) or quantum cascade lasers (QCLs). And in conjunction with highly sensitive and linear detectors, ICLs and QCLs are being integrated into gas analysis systems.

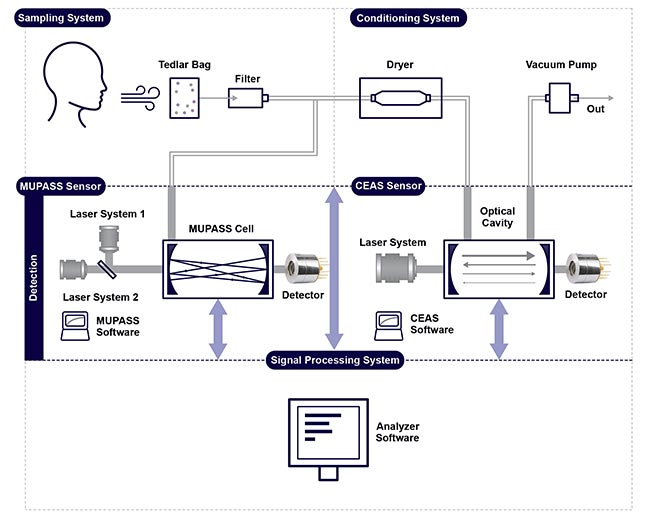

The SENSORMED optoelectronic breath analyzer, which can measure up to three gases via breath analysis. MUPASS: Multipass; CEAS: cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy. Courtesy of VIGO Photonics. Courtesy of VIGO Photonics.

Of course, these developments have expanded on the previous successes in sensing and spectroscopy within the medical arena. One of the earliest and most important IR techniques broadly used in medicine, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, uses a broadband (usually thermal) light source and a Michelson interferometer. In this method, a sample is placed in one of the interferometer’s arms and then an interferogram is recorded. Following Fourier transformation, an IR spectrum of the sample is resolved, where distinct features emerge at given wavelengths. These correspond to the energies of the absorbed photons, which in turn are suited for transitions between distinct rotational-vibrational quantum levels within the molecules. An FTIR spectrometer allows researchers to measure a broad IR spectrum of the sample simultaneously.

Therefore, this method has become indispensable for certain applications in laboratory analysis and is highly regarded due to new developments, such as the integration of highly sensitive, Peltier-cooled detectors made from mercury cadmium telluride or III-V-based Type-II superlattice compounds. They offer a similar resolution to previously prevalent liquid nitrogen cooled detectors, while being more applicable outside specialized facilities. New iterations of FTIR systems have also been introduced, such as FTIR microscopes, combining visible-light cameras with IR detectors for spectral measurements in specific points of the sample.

Take a breath

In terms of laser-based spectroscopic gas analysis, the identification of component biomarkers in human breath is of paramount importance in medicine. Apart from nitrogen, oxygen, or CO

2, which make up the bulk of breath volume, human breath consists of >3000 trace substances, whose elevated concentrations can indicate underlying health conditions. These gases are commonly known as biomarkers, which include, for example, formaldehyde for lung cancer; methane or ethane for oxidative stress (a chemical process present in many abnormal conditions due to an imbalance of free radicals); nitrogen oxide for asthma or rhinitis; carbonyl sulfate for hepatic failure or cystic fibrosis; and acetone for Type 1 diabetes, among many others.

Laser-based gas analysis in the MIR range can also be used in the detection of exotic gaseous species, due to its extremely high specificity.

However, this abundance of gaseous species poses a large challenge for traditional analytical devices. An absorption peak must be very carefully chosen to avoid the interfering signals from other molecules, especially those present in large quantities (e.g., carbon dioxide and water vapor). The MIR is ideal for this purpose with its well-separated absorption features.

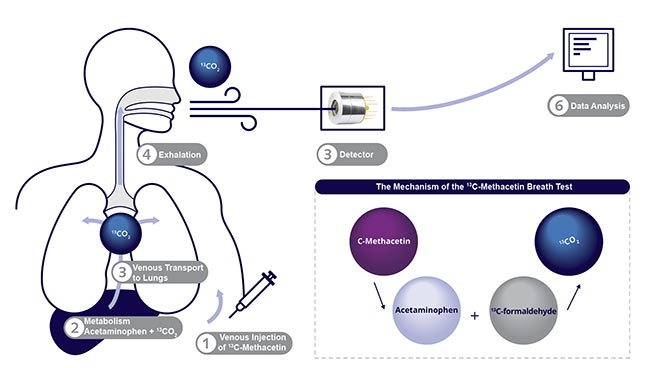

The principle of a 13C-methacetin breath test, which can serve as a warning of impaired liver function. Courtesy of VIGO Photonics.

Additional requirements for such devices are fast responses of up to a couple of minutes for a complete reading and a low limit of detection, because biomarkers are occasionally present in concentrations down to a single part-per-billion. The latter is strictly bound by the Bouguer-Lambert-Beer law, which states that the absorption of light by a solution is proportional to both the length of the optical path through the sample and the concentration of the absorbing substance. As a result, laser gas analyzers for human breath application normally use an optical cavity, in which the measured gas is placed. Several distinct techniques have emerged from this concept.

Multipass (MUPASS) spectroscopy uses mirrors on the cavity’s ends simply to enhance the optical path — up to several hundreds of meters for a tabletop device. Wavelength modulation spectroscopy adds a specific tuning of the laser — both in intensity and wavelength — to the process, which helps in noise rejection. The combination of these techniques is most commonly used in tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy. However, the cavity may also be of the resonant variety, in variations such as cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy or integrated-cavity output spectroscopy. The difference between these methods is the way that the output from the cavity is recorded.

More complicated systems are employed for cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS). For this method, a pulsed laser is used, and after a pulse enters the cavity with the gas, a radiation leak from it is recorded. Based on the leak’s intensity decline in time compared with an empty cavity, a concentration of the gas may be calculated. CRDS remains one of the most sensitive techniques for laser-based gas detection and has been verified by research groups to be suitable for breath analysis systems.

Aside from the optical path selection itself and the necessary signal processing (with noise rejection algorithms such as lock-in amplifications used on regular basis), strict attention must be paid to sample conditioning. Low limits of detection are usually only attainable at low pressures of the sample gas, which in practice reduces the challenge of pressure broadening of absorption features. Removing water vapor from the sample is also beneficial, because it removes the main source of interference in MIR spectroscopy. Even though the wavelength region that is normally chosen is located in an atmospheric transmission window (a region of the electromagnetic spectrum that can pass through the atmosphere), characterized by relatively low absorption by H

2O, significant interactions with most of the absorption features of biomarkers still occur.

Research collaborations

Laser-based systems have matured to the point where their utility has been thoroughly proved, and the first devices intended for commercial use are entering clinical trials. A project exemplifying these efforts was SENSORMED — a collaborative project between three Polish academic institutions and VIGO Photonics that reached fruition in 2018. The main result of this effort was a triple-band CRDS+MUPASS system for the measurement of three gases simultaneously. For nitric oxide, a CRDS system at 5.26 µm was chosen, whereas a bispectral MUPASS system was used at 2.25 µm for methane and 2.34 µm for carbon monoxide.

The best available detectors, such as mercury cadmium telluride with built-in immersion lenses for increased detectivity, along with high-fidelity cavities and an appropriate sample conditioning system (demoisturizing, negative pressure, and airflow velocity control) resulted in limits of detection between 30 and 400 parts per billion. The biomarkers that were detected indicated potential asthma, angina, stomach diseases, and elevated bilirubin levels in the blood, including Gilbert’s syndrome, Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Rotor syndrome, and Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

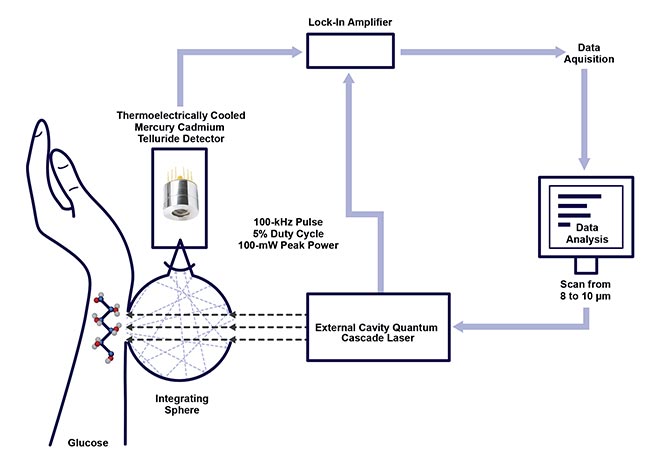

The concept of a MIR noninvasive glucose measurement on the skin using quantum cascade laser (QCL)-based spectroscopy. Courtesy of VIGO Photonics.

Laser-based gas analysis in the MIR range, due to its extremely high specificity, can also be used in the detection of exotic gaseous species, including isotope-specific CO

2, identified by the number of neutrons in the carbon atoms. Due to the specific metabolism processes that occur in conditions such as liver diseases or

Helicobacter pylori, a common stomach bacterial infection, solutions containing the isotope

13C can be ingested or injected, which allows for the ratio of

13CO

2/

12CO

2 to be measured, revealing the severity of the condition or lack thereof. Alternatively, ammonia can also be detected as an indicator of

H. pylori and simplify a potential second test for the condition.

Laser-based systems have the potential to provide fast and noninvasive measurements, for example, during annual checkups, and while they cannot practically replace classical diagnostics — due to existing, though reduced false-positive results — they can aid in preventive health care.

Glucose testing

In medicine, MIR laser usage has long been sought after for its potential use in noninvasive glucose sensing. Mitigating the need for finger pricking to obtain measurements of glucose levels would be widely welcomed by diabetes patients around the world. The basic challenge for IR radiation in this application is its limited ability to penetrate skin tissue. The composition of tissue is in itself a disadvantage, because water content interferes with signal detection. To counteract this, only glucose molecules lying close to the surface of the skin can be targeted, which is normally performed with high-power pulsed QCLs with wavelengths between 8 and 10 µm. In this region, glucose absorption lines are abundant and well defined, with relatively minimal water interference.

Using a pulsed laser with signal processing, such as lock-in amplification, could help achieve desired sensitivity and improve the limit of detection. Alternatively, shorter wavelengths between 2.5 and 3 µm can be used. Appropriate optics such as miniature integrating spheres are also required to collect the divergent light that exits the skin. The test results of certain devices have deemed thermal emission measurements to be more advantageous compared with back-scattered QCL radiation. This necessitates registering small changes in skin temperature that occur as a result of absorption by glucose molecules.

A similar approach can be used for identifying other substances, such as lactates in blood, which are indicators of tissue fatigue during training. For this to be broadly used in a wearable device, however, the final system would need to be miniaturized.

IR in dentistry

A more classical application of IR sensing in medicine is its use in dentistry. The proper use of a MIR laser and thermal detection can identify early tooth decay; a low-power pulsed laser is shone onto a tooth, and as a result, luminescence and thermal radiation are measured. Healthy teeth emit a different spectral signature than decayed teeth, and altering the parameters of the laser allows the radiation to penetrate varying depths, therefore detecting decay at and below the surface of the tooth. Lesions as small as 50 µm in diameter and 5 mm below the surface of the tooth can be detected, also due to high sensitivity and fast IR photodetectors.

Early detection of decay allows

remineralization therapy to be performed, avoiding more invasive and costly treatment. Another dental application of IR systems is the use of CO

2 lasers for anesthesia-free dental surgery. This method uses lasers emitting at 9.3 µm or 10.6 µm to cut through tooth structure, remove decayed tissue, and prepare and shape teeth for composite bonding. This surgery can be more comfortable and precise than traditional, drill-based procedures, but requires a very accurate control of the laser light — which is enabled by fast and sensitive mercury cadmium telluride or Type-II Superlattice detectors, and has been established in clinical settings.

IR sensing is becoming a critical tool in medical applications. The applications described showcase significant potential, especially in preventive health care and home-based diagnostics. Dentistry and laboratory analytics are already being used in clinical settings. For other use cases, however, significant work must be performed to overcome obstacles to reach commercialization. In the case of photonics, all the groundwork has been laid and the building blocks exist in the form of lasers, detectors, and verified measurement techniques. But for a final device to be convenient and sustainable, the optical systems must solve issues pertaining to size, power consumption, and heat generation.

Significant hope among researchers and developers has therefore been placed in photonic integrated circuits (PICs) for sensing at the MIR range. Attaining remarkable scalability and miniaturization of these systems would allow for widespread adaptation of MIR sensing in health care. But the full use of PICs in medicine must mature for a couple more years due to the ongoing clinical trials for systems designed for breath analysis or noninvasive glucose sensing. These trials serve as final real-world verification of the techniques. With future technologies such as PICs around the corner, researchers and companies alike may find increasing use cases of IR sensing in health care, and take advantage of these inherent capabilities to develop a complete solution for market.

Meet the author

Jedrzej Mijas has been working at VIGO Photonics as an application engineer since 2020, specializing in spectroscopy and gas sensing applications. Mijas earned a Master of Science at the University of Warsaw, where he gained broad theoretical knowledge and practical experience in IR optics. His expertise gained in academia was demonstrated by his construction of a TDLAS system for trace ethane detection in human breath for his master’s thesis; email:

jmijas@vigo.com.pl.