Full company details

Pureon AG

Kreuzlingerstr. 1

Kreuzlingerstr. 1

8574 Lengwil

Switzerland

From Circuits to Surfaces: Semiconductor Innovations Advance Precision Optics Fabrication

Photonics Spectra

Sep 2025Once operating in parallel technological spheres, optics and semiconductors are now converging in profound and transformative ways.RAVI BOLLINA, WILLIAM GEMMILL, TERRY KNIGHT, AND ADAM NIELSEN, PUREON

What were once distinct industries — optics, rooted in classical precision mechanics, and semiconductors,

defined by microelectronic miniaturization — are increasingly overlapping at the cutting edge of innovation. This convergence is not coincidental. Rather, it is the result of shared technical challenges and the cross-pollination of manufacturing techniques, driven in part by the requirements of optical components pushing beyond the limits of traditional processing methods. To meet these stringent requirements, manufacturers are increasingly adopting techniques originally established for semiconductor fabrication processes.

Courtesy of Pureon.

A growing set of applications that demand the strengths of both fields is another defining aspect of this burgeoning overlap. Semiconductor manufacturing is an established driver of process standardization, material innovation, and nanometer-scale precision. Now, as these capabilities move toward frontiers in optical fabrication, manufacturers are applying them to develop solutions. These range from freeform lenses for space telescopes to nanostructured surfaces in photonic integrated circuits (PICs) — which are gaining traction as scalable, high-performance solutions for telecommunications and advanced data processing. Elsewhere, adaptive and meta-optics are redefining beam control and wavefront shaping, enabling dynamic control of light with unprecedented precision in compact form factors.

The blurring of the line between semiconductors and precision optics is also evident in materials and techniques. For example, silicon carbide (SiC), traditionally used in power electronics and harsh- and extreme-environment applications, is being explored for use in high-performance optics. The material possesses

favorable thermal and mechanical stability, illustrating the growing crossover that is underway in materials science. Broadly, materials science is expanding through advanced crystals, nonlinear optical materials, and metamaterials. These areas of progress each serve to enhance wavelength coverage, optical efficiency, and durability.

Simultaneously, although located down the value chain from the crucial technology sectors to which precision optics are proving to be transformative, fabrication techniques are propelling growth upward in precision optics. Breakthroughs in subwavelength lithography, atomic layer deposition, and ultrafast laser machining

are direct enablers of the precision optics and photonics that are positioned at the forefront of science, industry, and defense. These fabrication methods enable the production of optics with nanometer-level precision, powering ultrasensitive sensors, high-power laser systems, and compact optical components for quantum computing and lidar.

Pureon’s IC OPTIC Puck product. The solution supports ultraprecise polishing of spherical and aspherical components and is machinable. It can be shaped into the mirror image of the final optic for improved surface control during polishing. Courtesy of Pureon.

One specific example, photolithography, formerly existed purely in the domain of chipmakers. Today, it is a foundational technique for creating subwavelength optical structures. Even semiconductor-driven disciplines, such as statistical process control, advanced metrology, and chemical-mechanical planarization are bringing utility to optics manufacturing, improving both quality and yield in increasingly complex component geometries.

These cross-industry implementations

are more than isolated adaptations. They reflect a deeper realignment of how optics and semiconductors are designed, fabricated, and refined. From lithography optics that shape every semiconductor node to polishing materials that transcend wafer fabs and telescope mirror production, manufacturers are redrawing the lines between these two industries. As precision, scale, and complexity push both fields to their limits, their shared challenges are forging shared solutions.

Still, challenges remain, particularly in the areas of thermal management, cost-effective mass production, and integration with existing electronic systems. However, the trajectory of precision optics and photonics is unmistakably upward.

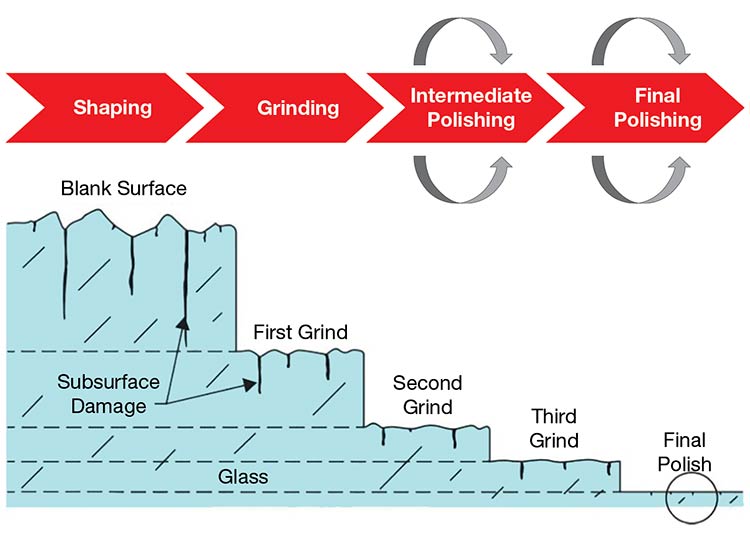

Precision polishing: Art and science

Achieving the required surface in advanced optics is one of the most demanding steps in the manufacturing process. It involves a complex set of challenges due to the extreme tolerances required for surface accuracy, smoothness, and shape fidelity. Even minute imperfections at the nanometer scale are apt to degrade optical performance, particularly in high-power laser systems, space telescopes, and interferometric instruments. Achieving such specifications requires highly controlled environments, advanced metrology, and sophisticated polishing techniques.

Breakthroughs in semiconductor consumables, such as polishing pads, often deliver value to precision optics applications and solutions. Courtesy of Pureon.

Techniques including magnetorheological finishing, ion beam figuring, and computer-controlled polishing are increasingly standard in production. Additionally, different materials, such as fused silica, sapphire, and calcium fluoride, respond differently to polishing processes. Avoiding subsurface damage or stress-induced birefringence becomes a challenge, often demanding customized approaches and/or distinct materials at this stage of production.

Defect control, particularly preventing

polishing residues and subsurface

contamination, is equally essential. Microscopic remnants of polishing compounds, such as cerium oxide particles, can embed in the optic surface and act as absorption sites under high-power laser illumination. This defect can significantly lower the laser-induced damage threshold and potentially cause catastrophic optic failure. Multiple studies show that polishing suspensions and pads can contribute carbon or abrasive residues, and plasma post-treatment may be needed to remove these contaminants and recover the laser-induced damage threshold.

Today, the challenges of maintaining uniform removal rates, avoiding edge effects, and achieving consistent surface quality are increasing significantly as optics become more complex in geometry

and application. This is especially true as freeform and aspheric surfaces become more common, which serves to compound

this challenge. The geometries of these optics, in particular, challenge conventional polishing methods due to their non-rotationally symmetric profiles, tighter tolerances, and more demanding functional requirements.

As a result, precision polishing is becoming less of an art than a science. More than ever before, it requires a deep understanding of material behavior, tool dynamics, and process adaptation.

In this context, the emergence of mid-spatial frequency errors represents one particularly persistent challenge.

Mid-spatial frequency errors

Mid-spatial frequency errors refer to surface irregularities with spatial wavelengths typically between 0.12 and 5 mm, situated between low-frequency form deviations and high-frequency roughness.

Often, the sub-aperture polishing or deterministic finishing processes are responsible for introducing these mid-spatial frequency ripples. In these processes, repetitive tool paths or oscillatory tool motion can generate periodic surface structures. Such features may not appear in standard figure measurements but can degrade optical system performance by inducing diffraction, increasing scatter, or reducing the Strehl ratio, especially in high-resolution imaging or high-power laser applications.

To manage these effects, manufacturers are implementing pseudo-random tool paths, incorporating dedicated smoothing steps, and using power spectral density-based metrology to monitor mid-spatial frequency content throughout the polishing and/or finishing processes. These strategies are essential to deliver optics that meet not just global shape requirements but also the localized surface quality needed for next-generation optical systems.

Coatings and metrology

Of the multiple processes initially developed for microelectronics and now enabling the creation of optical components with nanometer-level precision and complex geometries, atomic layer deposition has become the standard in the optics industry. It is used widely for modern optical coatings, enabling the deposition of conformal, pinhole-free films with precise thickness control at the atomic level. The method offers high value for producing high-performance antireflective coatings, interference filters, and durable protective layers on optics with challenging geometries.

In addition, these coatings offer excellent uniformity, environmental durability, and extremely low optical losses — all of which are vital qualities for advanced photonics applications such as high-power laser optics and integrated photonic circuitry. As a result, optical systems are becoming more compact, efficient, and integrated, opening new possibilities

in areas such as photonic computing, advanced sensing, and high-resolution imaging.

Precision metrology is another area where progress in the semiconductor

industry has spurred improvements needed to meet the stringent specifications of advanced optical components, from wafer inspection to gauging optical component quality. Many techniques deployed for the semiconductor industry are now widely applied to assess surface roughness, figure accuracy, and material uniformity in optical substrates and coatings. These include interferometry, white-light profilometry, scatterometry, and optical and atomic force microscopy.

The graphic shows a classic glass optic manufacturing process flow, from shaping to final polishing. Image adapted from Reference 2.

Courtesy of Pureon.

These test and measurement methods provide nanometer to subnanometer resolution, enabling manufacturers to detect and correct defects that could compromise optical performance. This is critically important in micro-optics fabrication. The demand for high-throughput, noncontact, and automated metrology solutions will soar as optics continue to shrink in size and increase in complexity, particularly in PICs and freeform optics. By leveraging the speed, precision, and scalability of semiconductor inspection technologies,

optical fabricators maintain tight tolerances and improve yield, quality, and repeatability across production cycles.

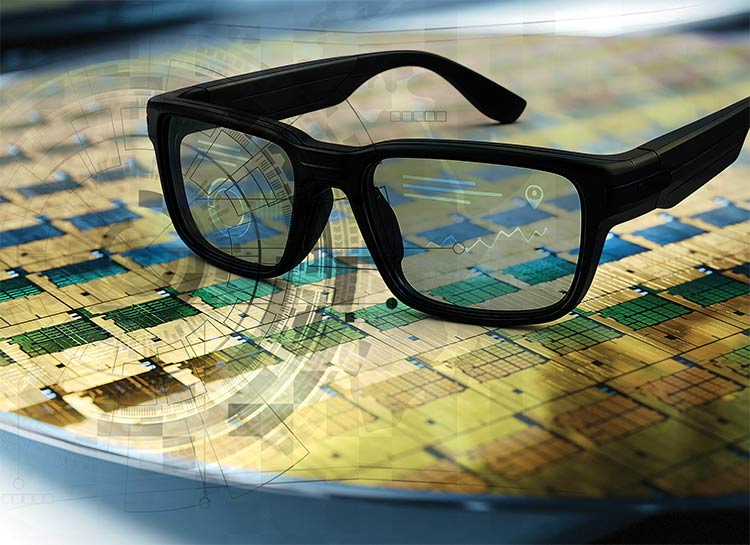

The age of augmented vision

The convergence of semiconductor-grade metrology, atomic-scale coatings, and precision optics is not merely theoretical — it is already transforming real-world technologies that bridge the digital and physical worlds. Nowhere is this more evident than in the accelerating field of augmented and mixed reality, where the demands for ultracompact, high-performance optical systems intersect directly with semiconductor innovation. Fundamentally, as display technologies shrink, computational power grows, and user expectations rise. The need for optics that meet nanometer-scale tolerances while remaining lightweight, durable, and scalable becomes paramount.

Meta’s Orion Glasses are a striking example of this convergence, spotlighting how semiconductor-driven precision is enabling a generation of wearable optics. The Orion augmented reality platform integrates micro-LED projectors into custom SiC optical elements, achieving exceptional miniaturization and optical clarity within an ultralightweight form factor. The system combines next-level display technology, eye and hand tracking, and AI-powered interfaces — each relying on precision optical engineering originally trialed and refined in semiconductor manufacturing. The Orion prototype similarly offers clear evidence that submillimeter component alignment, advanced coatings, and wafer-level tolerances have moved beyond the cleanroom to underpin the performance of consumer-facing devices.

Orion today remains a prototype. Still, it offers a glimpse into a future in which everyday devices will demand the same meticulous optical and material precision as the most advanced semiconductor fabs. It is a future in which the disciplines of optics and microelectronics are deeply

intertwined, driven by common challenges in miniaturization, thermal management, and system integration.

Bridging disciplines for high performance

Pioneering systems such as Meta’s Orion prototype exemplify the dissolution of the boundaries between microelectronics and precision optics. As mentioned, this same convergence is also transforming the materials and consumables that underpin advanced manufacturing. Indeed, the tools of precision are not limited to system-level breakthroughs — they are equally forged at the microscopic level, where surfaces are shaped, polished, and perfected.

Even advancements in semiconductor consumables, such as polishing pads and slurries, can often create direct value in the world of precision optics. For example, the IC1000 product from DuPont is among the most popular polishing pads on the market for semiconductor device fabrication. The product achieves consistent planarization and exhibits minimal defectivity and loss of global planarity, making it a widely used solution for chemical mechanical planarization processes.

Precision optics industry users can apply these same favorable qualities for ultraprecise polishing of spheres and aspheres. For example, Pureon has adapted the DuPont offering into a product that uses the same proprietary polyurethane blend in a configuration thick enough to support ultraprecise polishing of these components. The product, IC OPTIC Puck, is also machinable. It can be shaped into the mirror image of the final optic for highly conformal contact and improved surface control during polishing.

Of course, the benefits that derive from advancements such as these flow both ways; precision optics plays a critical role in photolithography, enabling the continued miniaturization of electronic components. Similarly, high-performance optical systems are essential for focusing

and directing deep-ultraviolet and extreme-ultraviolet light with exceptional accuracy. These optics must maintain

uniformity and stability under intense energy loads while achieving diffraction-limited performance to resolve features <10 nm.

Innovations in materials, coatings, and metrology have been key to advancing optical performance, allowing chipmakers to push the boundaries of Moore’s law. Now, as semiconductor nodes shrink further, the demands on optical systems in lithography will become even more stringent, making precision optics a foundational technology for the future of electronics manufacturing.

This cross-disciplinary innovation extends to abrasives. Cerium oxide,

which has historically been used in

dielectric planarization for semiconductors, is now undergoing reengineering

for optical-grade applications where surface integrity and cleanliness are paramount. Pureon’s line of ceria-based suspensions exemplifies this transfer of technology; these product formulations are designed to meet the specific needs

of high-performance optics manufacturing, offering stable chemical behavior, narrow particle size distributions, and high-purity compositions. By providing a balance of removal rate and surface quality, the products enable ultrasmooth finishes with sub-angstrom roughness

on materials including fused silica,

optical glass, and crystal substrates. This level of control is critical in applications such as high-power laser optics, space instrumentation, and advanced interferometric systems, where even nanoscale residues or defects can compromise

performance or reduce component lifetime.

Lingering challenges and solutions

In most cases, the desired shape and form of an optical part is achieved in the generation process, and final polishing is required to improve the surface quality and geometry and to avoid distorting the desired optical form. The instruments used in final polishing operations are commonly rigid form tools to which a thin polishing pad — referred to as a petal pad or foil — is applied.

The polishing pad material used in final polishing operations is typically a polyurethane type of material with a random pore structure imparted to the material during manufacturing. This random pore structure was initially developed to aid in slurry transport for increased material removal

1.

However, the inconsistent pore structure limits the pad material’s performance with respect to surface quality and polishing part-to-part consistency. In this case, the need is to achieve improved consistency in the polishing process via a highly controlled pore structure.

This challenge represents just one of many that the combination of semiconductors and precision optics is bringing to the fore. To help meet it, Pureon markets a urethane material solution that can be generated into complex 3D shapes not achievable by conventional petal pads, particularly for operations involving steep radii. This 3D form, used in conjunction

with computer numerical control or spindle polishing tools, can be dressed, regenerated, or modified several times during its lifetime.

Still, not all change is immediate. The use of cerium oxide-based polishing slurries, for example, is ubiquitous in the polishing of silicon-containing glasses, commonly used for precision optics. The cerium oxide abrasives are typically ~1 μm and can provide exceptional surface qualities for many applications.

However, as technology progresses and application demands increase the requirements for such optical surfaces, there is a need to improve process solutions that

include polishing slurry and pad. Pureon has aimed to address this challenge through its development of a <100-nm cerium oxide-based polishing slurry for the ultimate surface qualities in precision optics. The development highlights the need for industry to extend beyond the boundaries of traditional optical slurry manufacturing and the imperative to meet at the intersection with semiconductor-

derived breakthroughs to develop a solution.

An era of shared precision

The convergence between semiconductor

manufacturing and optical fabrication is no longer theoretical. Already, it is reshaping how precision components are designed, processed, and polished. What began as a limited transfer of knowledge between industries has evolved into a deeper structural alignment, where materials, metrology, and process controls developed for the semiconductor industry are solving long-standing challenges in optics.

This integration is not about one industry absorbing the other but about a shared pursuit of nanometer precision, consistency, and scalability. As optics grow more complex in shape and function, and as semiconductors push toward ever-smaller nodes and more integrated systems, the overlap between the two fields will only expand. From advanced polishing pads and ceria suspensions to atomic-level coatings and subnanometer metrology, the building blocks of next-generation optics are increasingly shaped by semiconductor-grade thinking.

Meet the authors

Ravi Bollina is the chief sales officer at Pureon and an executive board member. He holds a Ph.D. in engineering science and mechanics

from Pennsylvania State University and specializes in wide-bandgap semiconductor materials; email:

rbollina@pureon.com.

William Gemmill is chief innovation officer at Pureon and an executive board member.

He holds a Ph.D. in solid-state chemistry from the University of South Carolina and is

responsible for developing new technologies and commercializing new products; email:

wgemmill@pureon.com.

Terry Knight, technical services manager at Pureon, has more than 35 years of experience in the silicon wafers, disk drive, chemical mechanical polishing, and optics industries. Knight has a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from Arizona State University; email:

tknight@pureon.com.

Adam Nielsen is a product line manager at Pureon with more than 20 years of experience in technical sales and product management.

He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering from Brigham Young University and a Master of Business Administration degree from San Diego State University; email:

anielsen@pureon.com.

References

1. M.J. Kulp (Oct. 16, 2012). Polyurethane polishing pad. U.S. Patent No. 8288448. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

2. T.I. Suratwala (2018). Materials Science

and Technology of Optical Fabrication.

The American Ceramic Society (Wiley),

www.doi.org/10.1002/9781119423775.