The convergence of photonics and chip-based methods has enhanced microfluidics, as well as a variety of biological screening methods.

By Andreu Llobera

Offering compactness, efficiency, and automation in a single chip-size platform, lab-on-a-chip (LoC) technology has achieved remarkable progress during the last three decades.

Applications such as cell screening, cell sorting, and molecular diagnostics show unequivocally that optical and photonic techniques have gained significant traction in the biomedical sector.

LoC systems miniaturize and integrate the essential steps of an analytical assay, from the processing of raw clinical samples to the final isolation and quantification of target analytes, which often exist in trace concentrations. Today, the most advanced of these systems have been established as transformative platforms for both analytical sciences and clinical diagnostics.

A neuron superimposed on a chip. Chip-based imaging is enabling a new generation of diagnostics. Courtesy of iStock.com/jxfzsy.

Applications such as cell screening, cell sorting, and molecular diagnostics show unequivocally that optical and photonic techniques have gained significant traction in the biomedical sector. The popularity of optical and photonic techniques for these applications stems from the capabilities of high sensitivity, rapid analysis, and noninvasive, label-free interrogation. Furthermore, optical techniques offer exceptional spatial and temporal resolution, making them ideally suited for the study of dynamic biological systems in real time.

The use of micro-optics, waveguides, on-chip light sources and detectors, as well as novel photonic materials enables the integration into chip-based systems. In combination, these innovations support the creation of highly miniaturized, robust, and efficient sensing platforms.

But to deliver the best possible results, LoC systems must meet a set of stringent requirements, encompassing both performance and system design. These requirements include rapid operation, mechanical and chemical robustness, user-friendliness — even for nonspecialist users — and minimal reliance on external resources. Further, these systems should ideally incorporate self-contained reagents, include built-in or self-calibrating mechanisms, or eliminate the need for calibration altogether.

In their drive to meet these ambitious design goals, R&D scientists and engineers have pioneered groundbreaking advancements in two primary domains: microfluidics and detection methods.

Microfluidics is related to the handling of liquids — often biofluids — typically at the submicroliter scale. Its main aim is to detect a wide range of biomarkers indicative of a particular disease or condition. In traditional systems, chips that capture characteristics of biofluids have mostly been constructed using soft photolithography.

Continued miniaturization of components and complete systems has yielded significant advantages: reduced device size and weight, shorter time-to-result, minimized reagent consumption, and enhanced analytical sensitivity, precision, and throughput. Importantly, systems designers have succeeded in introducing these benefits into LoC architectures without drastically increasing the operational complexity or physical footprint of the systems. In addition, the improvement of compatible materials used in the fabrication of these systems is enabling end users to access a wider range of application fields. These improvements in materials are evident both in the variety of available materials and enhanced overall material quality.

Alongside innovations in microfluidics, the detection capabilities of LoC systems have also advanced significantly. Particularly in specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and limits of detection, these advancements have both contributed to and benefitted from a wide range of well-proven detection modalities. Optical/photonic, electrochemical, and magnetic approaches each offer distinct advantages, depending on the unique requirements of the application and the nature of the target analytes. These diverse sensing strategies continue to enable more precise and real-time monitoring of biological and chemical processes within miniaturized platforms.

Organ on a chip

Advancements in microfluidics and detection capabilities extend beyond LoC systems technology. A similar progression is underway in microfluidics for organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems.

Many members of the biomedical community, as well as the broader science community, view OoC systems as a natural evolution or a further specialization of the LoC concept. The core principle behind the OoC concept is to simulate the behavior of various cell types, organ models, and even multiorgan models under dynamic flow conditions and illumination strategies, thereby re-creating both physiological and pathological processes. These technologies aim to replicate the microphysiological environment of human organs on a chip, offering

a powerful alternative to traditional

in vitro and in vivo models.

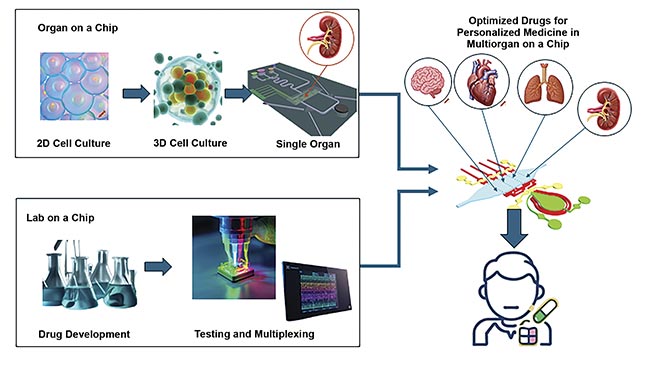

OoCs hold immense promise in areas such as drug testing, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. While they share many of the same underlying technology drivers as LoCs, they also face many of the same challenges: high production and operational costs, the need for application-specific customization, and reliance on multiple peripheral devices for environmental control, monitoring, and data acquisition. In addition, the specific culture conditions — for example, 3D versus 2D — necessitate an entirely unique fabrication path.

Another obstacle that LoC and OoC technology faces is that many of these systems still require external instrumentation for signal readout and data processing. This equipment is often heavy and bulky. While some level of integration with microfluidic networks has been achieved, dependence on off-chip equipment significantly undermines the portability, scalability, and cost-efficiency of these technologies. Looking ahead, this limitation also poses a significant barrier to the widespread adoption of LoC and OoC systems in clinical workflows. Overcoming this bottleneck is particularly important for decentralized or resource-limited settings, in which compact and user-friendly devices and machinery are essential.

The seamless integration of transducers capable of converting biochemical or chemical events into quantifiable signals directly on chip represents a crucial step in this context. The development of robust, miniaturized transduction mechanisms is pivotal for creating autonomous, self-contained analytical systems that do not require complex peripheral equipment.

Photonic lab/organ on a chip

While these advancements are contributing to new and more sophisticated

applications in biomedicine, the transformative impact of photonics, particularly advanced spectroscopic techniques, is already well recognized. Fluorescence-based imaging and sensing methods, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and techniques that use Raman spectra, for example, are commonplace in contemporary biomedicine and beyond. Light scattering and localized plasmon resonance are approaches that also fall into this category.

Techniques such as these have long proved to be invaluable in laboratory settings. However, the bulk and complexity of traditional optical instrumentation hindered its translation to portable and point-of-care platforms.

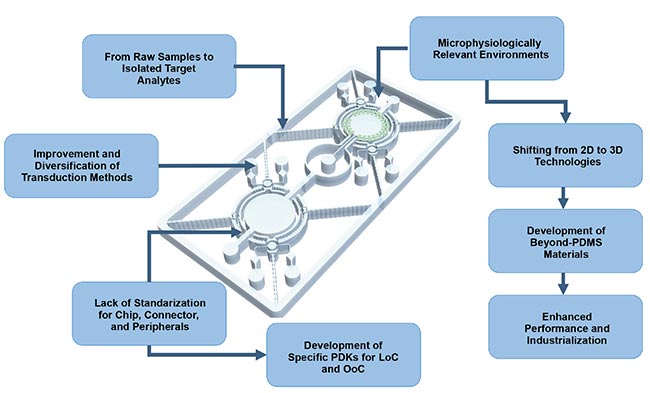

An overview of the current features and limitations of the lab-on-a-chip (LoC) and organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems, as well as the emerging trends driven by advancements in material platforms, the development of process design kits (PDKs), and increasing performance and system adoption. PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane. Courtesy of Silicon Austria Labs.

The convergence of photonics with LoC and OoC technologies — under the umbrella of photonic LoC and photonic OoC systems — offers a promising solution to this challenge. Indeed, the development of these systems is a compelling example of the widespread advancements in the field of integrated biosensing, which encompasses both optical and nonoptical methodologies. By embedding photonic components directly into microfluidic chips, these systems significantly reduce the size, complexity, and cost of conventional optical setups while maintaining, or even enhancing, analytical performance.

The integration of LoC technology with fluorescence-activated cell sorting is one illustrative example of this advancement. Traditional fluorescence-activated cell sorting systems, while powerful, are large and expensive and rely on complex fluidic and optical configurations. In contrast, photonic LoC-based flow cytometers can achieve scanning frequencies in the kilohertz range, enabling them to offer comparable analytical capabilities with a significantly reduced footprint. Such miniaturization paves the way for high-throughput, real-time cellular analysis in portable and accessible formats, which is essential for point-of-care diagnostics and decentralized testing.

Material considerations

One of the overarching challenges in developing LoC and OoC systems, and thereby increasing their market adoption, is in materials selection. Early devices evolved from microelectromechanical systems technologies, using bulk silicon micromachining and anodic bonding. In pursuit of cost reduction and manufacturing scalability, the field is transitioning toward polymer-based materials.

Currently, both lab-on-a-chip and organ-on-a-chip platforms face a common hurdle: translating sophisticated engineering into accessible, standardized tools for

real-world use.

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) remains the most commonly used material in academic LoCs and OoCs. It offers favorable biocompatibility, optical transparency, low cost, light weight, and chemical resistance. However, numerous studies highlight PDMS’ limitations: its high water absorption, nonspecific adsorption of biomolecules, porosity and gas permeability, and process upscaling complexity. While PDMS is well suited for prototyping and hypothesis-driven research, these drawbacks make it a suboptimal material platform for commercial and clinical translation.

A depiction of future advancements in biomedical research. Traditional 2D cell models are replaced by 3D cell cultures that better mimic the microphysiological environment of specific organs using OoC technology. In parallel, drug screening is becoming increasingly efficient and multiplexed through the use of LoC platforms. Created in https://craiyon.com. Courtesy of Silicon Austria Labs.

Thermoplastic polymers offer a more viable option for large-scale manufacturing, because fabricators can use established techniques such as injection molding to produce devices at lower costs and with greater reproducibility. Additionally, manufacturers can choose from a range of common thermoplastics, including polycarbonate, polymethylmethacrylate, polystyrene, and cyclic olefin polymer. An additional option, cyclic olefin copolymer, has emerged as one of the most promising materials for the scalable, low-cost production of microfluidic devices, due to its excellent optical clarity, low water absorption, and favorable chemical resistance.

Still, roadblocks exist in this area, too. Even though the price per device can be much lower, the substantial initial investment — justifiable only at high market volumes — continues to hinder the adoption of injection-molding technologies.

Moving toward in vivo relevance

For OoC applications, traditional 2D cell cultures fall short in replicating the complexity and physiology of human organs. Both researchers and industrial partners are increasingly adopting 3D cell culture models, which more accurately reflect in vivo gene expression patterns and therapeutic responses. Despite these improvements, both 2D and 3D models are commonly performed in static multiwell plate formats, which cannot replicate the dynamic and complex environment of living tissues.

As a result, animal models are still considered the gold standard in preclinical research. While animal models capture the full systemic complexity of drug interactions, they present significant limitations. These include in-application drawbacks, such as the phylogenetic divergence between animals and humans, as well as high costs, extended timelines, and ethical concerns.

These challenges underscore the need for more physiologically relevant, human-based in vitro systems — a need that is driving the development of advanced OoC platforms.

3D printing has emerged as a promising technology for fabricating OoC systems. Additive manufacturing offers high levels of accessibility and flexibility, as well as the potential for rapid prototyping. More specifically, it enables precise control over physiological parameters — such as fluid flow, shear stress, temperature, pH, and oxygen gradients — all of which are critical for mimicking human physiology.

Bioinks — the materials used in 3D printing — can be engineered to replicate biological environments. These materials range from photocurable resins and thermo- and photopolymers to hydrogels and composites with embedded living cells and/or biomolecules. Additionally, various additive manufacturing techniques and technologies — broadly categorized into inkjet printing and photopatterning methods — offer potential for use.

As with the OoC technology that additive manufacturing is helping to advance, industry has also achieved significant milestones in this technology. Companies such as SÜSS MicroTec have achieved breakthroughs in inkjet printing, while others, including Nanoscribe, Heidelberg Instruments GmbH, and UpNano, have pioneered innovations in high-resolution two-photon polymerization. These companies have helped to advance a technology that continues to face challenges in becoming a cost-effective, high-throughput approach for producing disposable cartridges or consumables at an industrial scale.

Lack of standardization

To ensure the practical deployment and broad adoption of LoC and OoC technologies, system designs must prioritize both robustness and reliability. Standardization — another necessary quality — remains one of the most significant barriers to the commercial exploitation of these technologies. Currently, both LoC and OoC platforms face a common hurdle: translating sophisticated engineering into accessible, standardized tools for real-world use.

Future efforts, then, must prioritize the development of integrated, compact detection modules, cost-effective manufacturing techniques, and modular designs that can be easily adapted across a range of applications.

The development of standardized process design kits (PDKs) for LoC and OoC platforms could have far-reaching effects on the research, development, and industrialization of these technologies. The adoption of standardized LoC and OoC PDKs would bridge the gap between academic research and industrial manufacturing by establishing a shared technical framework and design workflow.

A PDK-enabled standardized technical and design workflow for LoC and OoC systems could be especially transformative in sectors such as health care, where a need exists for rapid, reliable, and cost-effective diagnostics. It could enable cloud-based design automation, collaborative development platforms, and digital marketplaces for reusable microfluidic components and subsystems.

In this way, PDKs have the potential to transform the LoC and OoC landscape, shifting it from a domain dominated by custom, one-off prototypes to a scalable, industrial-grade platform. This evolution would greatly enhance the reliability, affordability, and global accessibility of LoC and OoC technologies, yielding far-reaching benefits across both expected and unexpected sectors.

Industrial implementation

LoC technologies are already driving increased innovation in industrial sectors such as pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and clinical diagnostics. Devices such as QIAGEN’s QIAxpert instrument enhance laboratory efficiency by providing rapid, high-throughput analysis of nucleic acid samples — an essential function for quality control in biomanufacturing and genomic research.

Similarly, Bosch’s Vivalytic platform simplifies molecular diagnostics via a compact, user-friendly design and rapid multiplex testing capabilities. These qualities make it a suitable solution for point-of-care applications and decentralized health care. Meanwhile, OoC technologies from Emulate, MIMETAS, InSphero, and other companies are gaining traction. These solutions mimic human organ functions in vitro, offering more physiologically relevant models for drug discovery, toxicity testing, and disease modeling.

Looking ahead, the integration of AI-driven data analysis, personalized medicine approaches, and scalable multi-OoC systems is expected to further transform industrial R&D pipelines. At the same time, it will reduce reliance on animal models and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

Meet the author

Andreu Llobera, Ph.D., is the head of Research Unit Photonic Systems at Silicon Austria Labs in Villach, Austria. He earned a Ph.D. in physics in 2002 and has co-authored more than 145 articles. Llobera’s research interests include photonic lab-on-a-chip technologies, polymer micro-optoelectromechanical systems, and photonic integrated circuits; email: andreu.llobera@silicon-austria.com.