Arash Aghigh and Francois Legare, National Institute of Scientific Research, Canada

In biological research, the visualization of tissue structures is critical for understanding their function as well as in tracking the progression of diseases in various stages. Second-harmonic generation (SHG) and polarization-resolved SHG (P-SHG) microscopy provide powerful, noninvasive alternatives to techniques such as fluorescence microscopy, cryogenic electron microscopy, and x-ray crystallography that enable the visualization of tissues without external labels or complex preparation, thus preserving sample integrity.

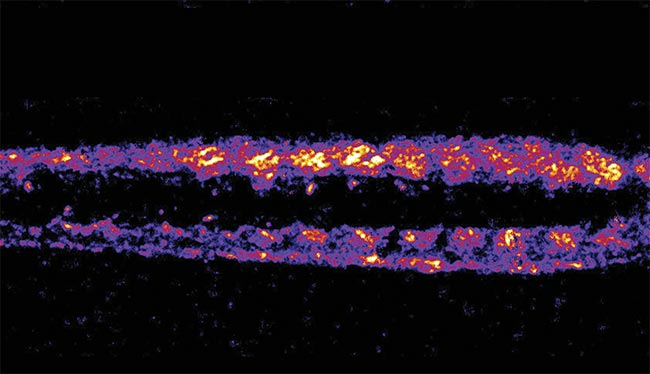

A denoised second-harmonic generation (SHG) image of zebrafish muscle using machine learning, revealing explicit fiber patterns with reduced noise. Adapted with permission from Reference 2.

SHG microscopy involves a nonlinear optical process in which two photons interact with non-centrosymmetric materials, generating a photon with half the wavelength. This effect is observed in biological structures, such as collagen, muscle fibers, and neurons, making SHG ideal for imaging these biological structures.

Using SHG microscopy for biological purposes dates back to the 1980s, when collagen fibers in a rat tail tendon were studied. Then in the early 2000s, it was shown it could be used for high-resolution tissue imaging using laser scanning.

P-SHG further enhances this approach by adding polarization sensitivity, revealing more profound insights into the alignment and organization of fibrous structures such as collagen in the extracellular matrix (ECM), a 3D network of proteins and other molecules that surround and support cells and tissues1. These features are valuable for studying processes such as fibrosis and cancer progression.

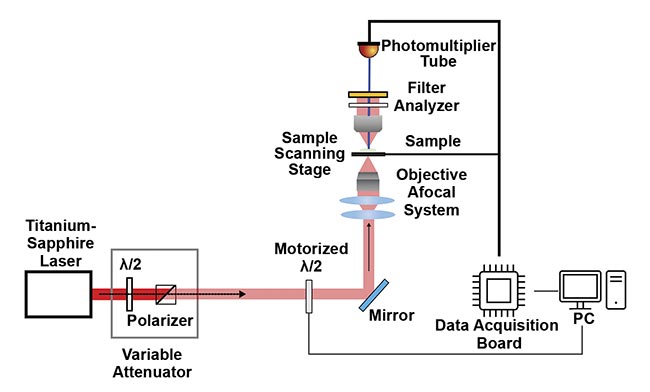

Despite their advantages, SHG and P-SHG face challenges in practical implementation, particularly the trade-off between image quality, laser power, and imaging time (Figure 1). High laser power risks damaging samples, whereas low power leads to noisy, unclear images. In addition, the acquisition of high-resolution images over large areas can be slow, leading to photodamage with prolonged exposure2. Data analysis is another challenge because the intricate images generated in the SHG process require extensive manual interpretation on the part of researchers, which is time-consuming and error-prone3.

Figure 1. A combined second-harmonic generation (SHG) and polarization-resolved SHG (P-SHG) microscopy setup uses a titanium-sapphire laser as the excitation source, passing through a polarizer and a variable attenuator for power control. A motorized half-wave plate (λ/2) enables automated polarization adjustments for the P-SHG imaging. The SHG and P-SHG signals from the sample are filtered and analyzed before detection using a photomultiplier tube. The sample is scanned using a motorized stage, and the resulting data is processed using a data acquisition board and displayed on a connected PC. Adapted with permission from Reference 1.

Machine learning can remove some of the subjective interpretation of images and improve the accuracy of results. Overall, machine learning algorithms can help enhance image quality, acquisition speed, and data analysis.

Enhancing SHG and P-SHG

Integrating machine learning into the microscopy workflow enables more efficient processing and analysis of complex images, significantly enhancing image quality through advanced denoising techniques, evening out pixel value and reducing blur and discoloration in the field of view.

Traditional noise reduction methods often involve filtering, which can obscure critical structural details in images. Machine learning offers more sophisticated solutions for preserving these details, such as collagen fibers.

An example is content-aware image restoration (CARE 2D), a supervised learning model for image denoising4. CARE 2D requires pairs of noisy and high-quality reference images for the training. By learning the differences, CARE 2D can effectively remove noise from new images while retaining the essential biological structures. This method works well in controlled laboratory settings, where researchers and scientists have high-quality reference images at their disposal.

In cases in which high-quality reference images are unavailable, Noise2Void (N2V 2D), a self-supervised learning method, effectively denoises images by learning noise patterns within the images themselves5. This approach considers the content within single images taken from a single microscope. The method is instrumental when working with rare or delicate samples such as thin mammary gland and muscle samples, for which minimizing the laser exposure is critical.

These advanced machine learning models allow for more accurate and efficient imaging by addressing noise reduction challenges without sacrificing structural integrity. Beyond improving image quality, machine learning can also play a critical role in accelerating the overall imaging process, especially when capturing high-resolution images over large tissue areas, which is time-consuming.

Faster acquisition times

Machine learning can significantly accelerate imaging, which is important for both biomedical and research purposes, because high-resolution imaging of large tissue areas can be a protracted process. In P-SHG microscopy, this challenge is even more significant because multiple images, usually 3 to 18 images, are needed to analyze the fiber alignment with different laser polarizations6.

Enhanced superresolution generative adversarial networks (ESRGANs) address the challenge of time-consuming high-resolution imaging by allowing researchers to quickly capture low-resolution images and upscale them to high resolution using machine learning algorithms6. ESRGAN, pretrained on pairs of low- and high-resolution images, employs two neural networks in competition: a generator that creates high-resolution images from low-resolution inputs and a discriminator that distinguishes between the generated images and real high-resolution images7. Through this adversarial exercise, ESRGAN learns to produce remarkably detailed images that resemble accurate high-resolution images, significantly accelerating the imaging process. As a result, the need for time-consuming high-resolution image acquisition can be bypassed without compromising the quality required for detailed analysis.

For example, in developmental studies of mouse mammary glands, applying general adversarial networkbased upscaling reduced imaging time from 4.5 h to just 13.5 min — a 95% reduction6.

This acceleration enables researchers to conduct more extensive studies and process more samples in less time, thereby significantly enhancing the throughput of experiments. As the volume of data increases, so does the complexity of its analysis, creating a demand for more efficient, automated analysis tools.

Quantitative data analysis

Traditionally, analyzing complex images generated by SHG and P-SHG microscopy has been a manual process that requires experts to interpret the tissue patterns and structures. This approach is lengthy and prone to variability.

Machine learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), helps automate this procedure by learning to recognize and classify patterns in images. CNNs can be trained on labeled data sets to identify specific features such as normal versus abnormal tissue structures, fiber orientations, or areas of high collagen density. Furthermore, through transfer learning, in which models pretrained on large data sets are fine-tuned for SHG and P-SHG data, researchers can accurately distinguish between healthy and diseased tissues with less computational effort.

In cancer research, deep learning models have shown high accuracy in differentiating between normal and tumor-bearing mammary glands3 in one study and in a separate study involving breast tissues8. By detecting subtle collagen changes, machine learning improves our understanding of tumor progression and interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment.

By streamlining data interpretation and reducing variability, machine learning improves imaging quality and transforms the workflow in biological research, allowing researchers to focus on deeper analyses and discoveries.

Applications across diverse tissues

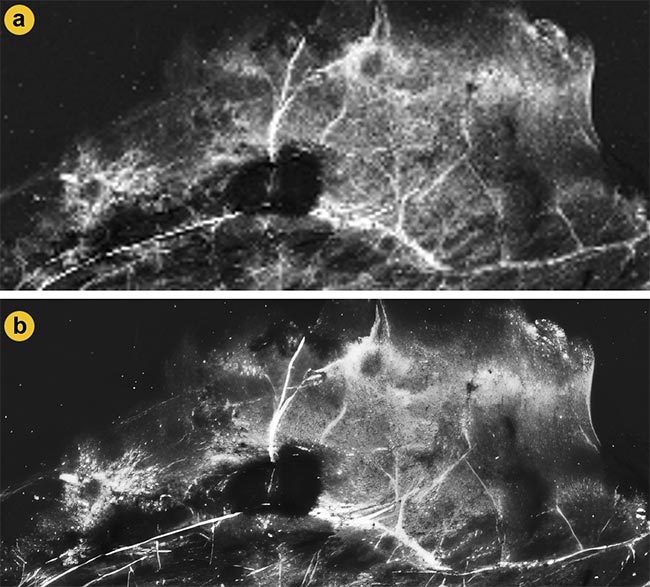

ESRGAN effectively reduced the SHG imaging time in mouse mammary gland ECM studies, preserving structural details (Figure 2). This technique is applied to other fibrous tissues to maintain image clarity without requiring extensive imaging time.

Figure 2. A comparison of second-harmonic generation (SHG) images from mammary gland samples before and after enhanced superresolution generative adversarial networks (ESRGANs) upscaling. Low-resolution SHG images captured from the sample (a). The same SHG image after 16× upscaling with ESRGAN enhances the resolution and clarity for further SHG and polarization-resolved SHG (P-SHG) analyses (b). Adapted with permission from Reference 6.

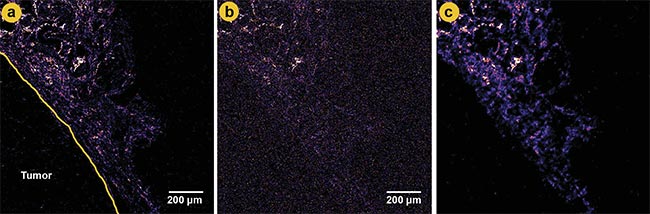

CARE 2D has demonstrated strong performance in analyzing collagen fibers, which play a critical role in tissue structure and function, in the ECM (Figure 3). The ability of this model to denoise images while preserving fine structural details makes it ideal for analyzing these delicate fibers under low signal-to-noise conditions, and its utility could extend to tissues such as the skin and bone, where collagen integrity is essential for health.

Figure 3. A comparison of second-harmonic generation (SHG) images at different laser power levels and denoising. A ground truth image of a tumor boundary in mammary gland tissue using higher laser power (a). A low-power image with significant noise (b). A denoised image using content-aware image restoration (CARE 2D), showing improved clarity and reduced noise (c). Adapted with permission from Reference 2.

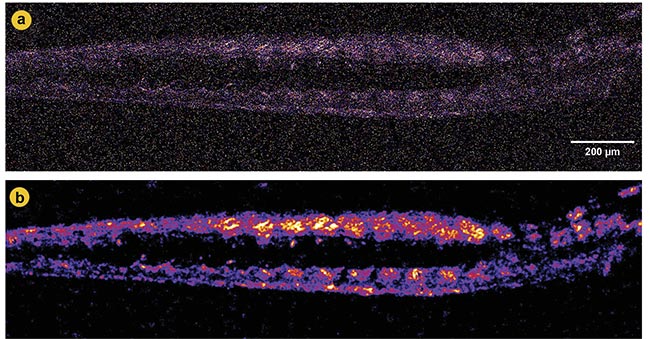

In contrast, N2V 2D excels in denoising zebrafish muscle tissue, particularly in the absence of reference images, which is advantageous for delicate or rare samples (Figure 4). This technique is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the muscle fiber details while minimizing laser exposure. Its adaptability to other soft tissues highlights its broad applicability to muscle disease research.

Figure 4. Second-harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of zebrafish muscle before and after denoising. A noisy SHG image with obscured structural details (a). A denoised image using Noise2Void (N2V 2D), revealing more explicit muscle fiber patterns and reducing noise (b). Adapted with permission from Reference 2.

These examples illustrate how selecting appropriate machine learning techniques for each tissue’s specific characteristics ensures the best outcomes in SHG imaging and analysis.

Applications in neuroscience

The adaptability of machine learning across different biological tissues extends to neuroscience, in which understanding the structure and connectivity of neural networks is crucial. SHG microscopy can visualize microtubules in neurons, which are critical components of axons and dendrites and are projections that allow neurons to communicate1. By applying machine learning-enhanced denoising and analysis techniques, researchers can track changes in neural fibers over time, offering valuable insights into neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Furthermore, machine learning can automate the quantification of axonal fiber alignment and density, aid in the early detection of neural degradation, and assess the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

The potential of machine learning to enhance imaging and analysis in neuroscience mirrors its broader impact across diverse tissue types. Whether in the muscle, ECM, or neural networks, algorithm-driven microscopy techniques can visualize complex structures with greater clarity, speed, and accuracy.

SHG’s future

The intersection of machine learning and SHG microscopy is a rapidly evolving field, and researchers perceive several promising avenues for integration in future development. Hybrid machine learning models could combine the strengths of supervised and self-supervised learning, adapting to different imaging conditions and sample types. Such models would offer flexibility and optimize the image restoration for various applications.

Adaptive imaging systems integrate machine learning directly with imaging hardware. By adjusting parameters such as laser power and exposure time and focusing on real time based on feedback from machine learning algorithms, these systems can optimize image quality while minimizing photodamage. These adaptive systems would be especially beneficial for live-cell imaging, in which maintaining cell viability is crucial.

Multimodal imaging and data correlation could involve combining data collected from SHG and P-SHG microscopy with the data gathered from other imaging techniques, such as fluorescence microscopy or Raman spectroscopy. Machine algorithms can correlate data from different sources, providing a more comprehensive understanding of tissue structure and function. For example, correlating the collagen structure from SHG images with protein expression patterns from fluorescence images could yield insights into disease mechanisms.

Real-time tissue classification using machine learning could enhance and accelerate clinical diagnostics and intraoperative procedures. Immediate feedback on tissue type and health status, such as for potential patients with cancer, during imaging sessions would enable faster decision-making and potentially improve patient outcomes.

Data-driven models will naturally improve over time as more data becomes available. Based on the evolution of AI and machine learning in many contexts, continuous learning from an ever-growing repository of images will enhance the accuracy and generalizability of machine learning models. This will be true when experimenting with different tissues and conditions.

In a broad sense, machine learning can transform SHG and P-SHG microscopy by overcoming significant challenges in image quality, acquisition speed, and data analysis. Advanced algorithms allow researchers to obtain high-quality images and efficiently extract meaningful information.

The recent awarding of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics to John J. Hopfield and Geoffrey E. Hinton, pioneers of machine learning and artificial intelligence, underscores the pivotal role of these technologies in advancing physics. The future of microscopy lies at the intersection of technology and biology, where innovations in machine learning and optics will continue to push the boundaries of what is possible, leading to breakthroughs in fields ranging from developmental biology to neuroscience and disease diagnosis.

Meet the authors

Arash Aghigh is a Ph.D. candidate at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (Canada), specializing in biomedical nonlinear optical microscopy and imaging system design. His research focuses on advancing second-harmonic generation microscopy through machine learning applications, improving imaging quality, and enhancing data analysis; email: [email protected].

François Légaré is a chemical physicist who specializes in developing novel approaches for ultrafast science and technologies as well as biomedical imaging with nonlinear optics. He has a Ph.D. in chemistry. Since 2013, he is full professor at the Energy Materials Telecommunications Research Centre of the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS-EMT); email: francois.[email protected].

References

1. A. Aghigh et al. (2023). Second harmonic generation microscopy: a powerful tool for bio-imaging. Biophys Rev, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 43-70.

2. A. Aghigh et al. (2024). A comparative study of CARE 2D and N2V 2D for tissue-specific denoising in second harmonic generation imaging. J Biophotonics, Vol. 17, No. 6, e202300565.

3. A. Aghigh et al. (2023). Nonlinear microscopy and deep learning classification for mammary gland microenvironment studies. Biomed Opt Express, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 2181-2195.

4. M. Weigert et al. (2018). Content-aware image restoration: pushing the limits of fluorescence microscopy. Nat Methods, Vol. 15, No. 12, pp. 1090-1097.

5. A. Krull et al. (2020). Probabilistic Noise2Void: Unsupervised Content-Aware Denoising. Front Comput Sci, Vol. 2, No. 5.

6. A. Aghigh et al. (2024). Accelerating whole-sample polarization-resolved second harmonic generation imaging in mammary gland tissue via generative adversarial networks. Biomed Opt Express, Vol. 15, No. 9, pp. 5251-5271.

7. X. Wang et al. (2018). ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv, arXiv:1809.00219.

8. K. Mirsanaye et al. (2022). Machine learning-enabled cancer diagnostics with widefield polarimetric second-harmonic generation microscopy. Sci Rep, Vol. 12, No. 1, p. 10290.