Radiopharmaceuticals with localized effects can be produced by light beams, releasing radioactivity into cancer tumors for imaging and treatment.

By Antoine Courjaud and Dimitri Batani

A radioisotope is an unstable atomic nucleus that undergoes radioactive decay, or more simply, a change in nuclear structure with the simultaneous emission of radiation. Radioisotopes can now be generated using lasers, which could help meet the rapidly increasing demand for medical radioisotopes and allow the production of novel radioisotopes to adapt to a variety of medical conditions, and to novel diagnostics requirements.

Radioactive particles can be targeted with light in cancer therapy. Courtesy of iStock.com/wildpixel.

Radioisotopes are distinguished by the type of emission that they produce, which can be either gamma-ray photons or particles such as electrons, positrons, or alpha (α) particles. They also differ in their lifetimes. In all cases, the number of a given type of radioisotope decreases over time due to decay, following an exponential law:

where No is the initial number of radioisotopes, t is time, and T is the lifetime.

Radioisotopes have widespread applications in modern medicine, both for cancer treatment and diagnostics. Nuclear medicine is increasingly moving toward the use of radioisotopes with short lifetimes, which are likely to cause less damage to healthy tissue. Yet, despite the promise, their use remains limited due to the specialized facilities that are required to produce them. But implementing a laser-based approach in the experimental stage may enable the adoption of radioisotopes in far more diverse environments.

The effective implementation of laser-driven radioisotope production will require both high-repetition-rate laser systems and corresponding advancements in target technology and diagnostics.

For therapy, radioisotopes are usually linked to a chemical compound forming a radiopharmaceutical (radioactive drug) that is preferentially absorbed by tumor tissue. Then, the radioisotope decays, emitting a particle that deposits its energy in nearby cells, potentially destroying them. In this case, the emitted particle must have a very short penetration range to ensure that it is absorbed within the tumor without damaging the surrounding healthy tissue. In this sense, α-emitting radioisotopes are particularly effective due to the minimal penetration in the matter of α particles. Beta-emitting radiopharmaceuticals, which emit low-energy electrons, are also increasingly used in cancer treatment.

Apart from therapy, radioisotopes are also important for diagnosing cancer and other diseases. Typically, positron emission tomography (PET) uses radioisotopes that decay by emitting positrons, which collide with electrons, producing two gamma ray photons, allowing image reconstruction that can reveal metabolic or biochemical changes in tissues.

But in a relatively new field, theranostics, radioisotopes — often a pair of different radioisotopes — are used simultaneously for both diagnosis and therapy.

An exploding market

The demand for radioisotopes is currently surging, mainly driven by their applications in medicine. According to a recent study by the European Nuclear Society, the demand for medical radioisotopes is expected to triple between now and 2030 (Figure 1)1.

Figure 1. A projected increase in the demand of radioisotopes used for therapy between 2020 and 2040. Courtesy of the European Nuclear Society.

Today, there are two predominant ways to produce radioisotopes:

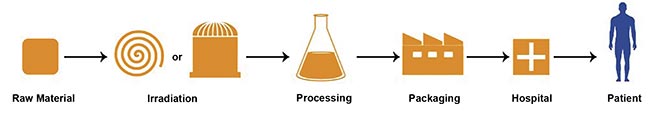

using nuclear reactors or cyclotrons (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The supply chain for radiopharmaceuticals. Courtesy of PALLAS.

Nuclear reactors are used to produce radioisotopes by irradiating a precursor material with the intense neutron flux that is inside the reactor. Examples of radioisotopes widely used in cancer treatment and produced via neutron irradiation include β- emitters, such as lutetium-177 and yttrium-90, which are used for radionuclide therapy targeting large or diffuse tumors. Another example is actinium-225, an α-emitter employed in high-precision internal radiotherapy for cancer treatment.

The second approach to radioisotope production is based on the use of proton beams accelerated inside a cyclotron — a particle accelerator that propels a beam of charged particles in a circular path. The beam is directed onto a target, where nuclear reactions take place, transmuting the precursor material into the desired radioisotope. An important example is fluorine-18, which is produced by irradiating oxygen, i.e., water, with protons. Fluorine-18 decays into oxygen-18 while emitting a positron, making it a key isotope for PET. Its short half-life (110 min) ensures that positron emissions occur rapidly during the PET scan, while the radioactivity dissipates in a short time, reducing the risk of damage to healthy tissues.

Alpha-particle beams

Another approach, which is currently mostly experimental, involves the production of radioisotopes using α-particle beams: two protons and two neutrons bound together. Today, radioisotopes produced by α particles are not widely used in medicine, despite their promising properties, because only a few cyclotrons worldwide are capable of accelerating α-beams with the necessary energy and intensity for their production. The nuclear reactions that generate these isotopes typically require α particles with energies >10 MeV, which can only be achieved with specialized cyclotrons such as ARRONAX (Accelerator for Research in Radiochemistry and Oncology in Nantes Atlantique, located in France) or U-120M (located in the Czech Republic).

A notable example is astatine-211 (²¹¹At), an α emitter with significant medical potential, due to its highly localized energy deposition. Currently, the supply of ²¹¹At is limited because it is primarily obtained as a by-product of nuclear weapons development. The current production levels are only sufficient for preclinical studies and limited clinical trials. However, ²¹¹At can also be synthesized by irradiating bismuth-209 (209Bi) with α particles, which could offer a scalable production method in the future.

Reaching production limits

On the one hand, the current situation is characterized by a sharp increase in the demand for radioisotopes, and a stagnation in production capacity on the other.

Research reactors remain the primary source of around 35 medical radioisotopes, with only 10% being produced using cyclotrons. Among these isotopes, molybdenum-99 accounts for the largest share, being used in ~85% of nuclear medicine procedures worldwide for diagnosing cancer, as well as heart, brain, and bone diseases — amounting to up to 50 million nuclear medicine procedures per year.

However, nuclear reactors are complex and expensive machines, costing between €600 million and €800 million, which is beyond the typical budget of research facilities. Currently, only about 25 countries operate research reactors that actively produce radioisotopes for medical applications.

Radioisotopes are distinguished by the type of emission that they produce, which can be either gamma-ray photons or particles such as electrons, positrons, or alpha (α) particles.

In Europe, four reactors are currently responsible for most of the continent’s medical radioisotope production: HFR, in the Netherlands; BR2, in Belgium; LVR-15, in the Czech Republic; and Maria Reactor, in Poland.

The challenges associated with nuclear reactor-based production include high installation costs, complexity, security issues, and an aging reactor fleet, which threatens long-term supply.

On the other hand, α-particle cyclotrons are also complex and costly, which has limited their widespread adoption until now. In contrast, proton cyclotron technology is well established, providing machines that are relatively affordable (a few million euros). However, proton cyclotrons can only produce a limited range of radioisotopes.

There is a need for new, accessible, and cost-effective production technologies that can be widely distributed across different regions. Such an approach would reduce material loss during transport due to radioactive decay and enhance safety by minimizing the risks associated with transporting radioactive materials.

Laser: A versatile approach

In 2000, for the first time, an experiment reported the generation of intense and tightly collimated beams of energetic protons by irradiating thin solid foils with a petawatt laser1. This physical process was named target normal sheath acceleration (TNSA).

A significant fraction of the laser energy (a few percent) can be converted into the energy of the proton beams, allowing the generation of highly intense beams containing a large number of protons.

More recently, such proton beams have been used to generate other particles in a cascade reaction. When protons are directed at beryllium or lithium “catcher” targets, neutrons can be produced, while when protons interact with a boron-containing catcher, they can trigger the proton-boron fusion reaction, releasing three α particles.

Several experiments on proton-boron fusion have been conducted in recent years, both to explore the feasibility of hydrogen-boron fusion for energy production and to study the potential for high-brightness α-particle sources2.

Laser radioisotope production

As a result of these studies, the idea has emerged to use laser-driven particle sources for the generation of medical radioisotopes. The key advantage of this approach is that, with minor modifications — mainly concerning the type of target materials used — the same setup can be adapted to produce protons, neutrons, or α particles. This means that, in principle, lasers could be used to produce a wide range of radioisotopes requiring different particle interactions.

Another crucial advantage is that laser technology is becoming increasingly accessible and cost-effective. This raises the possibility of future radioisotope production centers based on laser-driven systems that are easy to operate, affordable, and geographically widespread.

Such facilities could enable the on-site production of short-lived radioisotopes near their final point of use, such as hospitals and research centers, thereby minimizing losses due to radioactive decay and reducing the risks associated with transportation.

Recently, an international team led by researchers from Centre Intense Lasers and Applications (CELIA) laboratory at the University of Bordeaux conducted an experiment to investigate the feasibility of laser-driven sources for radioisotope production3.

The study specifically focused on the production of scandium-44, a positron-emitting isotope with a short half-life (<4 h) and simultaneous γ-ray emission only at relatively low energy. These characteristics make it an ideal candidate for PET imaging, because it minimizes collateral damage to healthy cells.

The experiment was conducted using the petawatt laser VEGA, manufactured by Amplitude Laser, at the Centro de Láseres Pulsados (CLPU) in Salamanca, Spain. This laser delivers short femtosecond pulses at a wavelength λ = 810 nm, with an energy of ~25 J/pulse (Figure 3). The laser was focused on thin aluminum “pitcher” foils (6 µm thick), producing a proton beam with energies reaching up to ~15 MeV. These protons were then directed onto a calcium silicate catcher target, where scandium-44 was generated through the nuclear reaction: p+44Ca → 44Sc+n.

Figure 3. The laser VEGA in Salamanca, Spain, developed by the French laser company Amplitude. Courtesy of Amplitude.

A germanium detector was used to analyze the gamma-ray spectrum of the irradiated calcium silicate sample (Figure 4). The spectrum revealed a clear peak at 1157 keV, the characteristic emission line of scandium-44. Additionally, a small amount of scandium-48 was detected as a minority isotope.

Figure 4. A gamma-ray spectrum obtained in the experiment at Centro de Láseres Pulsados (CLPU). Courtesy of CELIA laboratory/University of Bordeaux.

By calibrating the gamma-ray detector, the researchers determined that the experiment produced ~105 scandium-44 atoms per laser shot, corresponding to an activity of ~2 Bq (where 1 Bq (Becquerel) = 1 decay/s).

While this experiment demonstrated the feasibility of laser-driven radioisotope production, the current production rate is still far below what is required for medical applications. For reference, a single PET scan requires injecting a dose in the patient equivalent to an activity of ~50 MBq.

Producing such a number requires using laser systems working at a high repetition rate, in order to accumulate many shots on the same catcher material. Meanwhile, the parameter of the laser and pitcher target must be optimized to produce more protons in the good energy range and optimize the catcher target. For instance, in the case of scandium-44, this implies using a catcher enriched in calcium-44 instead of natural calcium.

By using a target rich in calcium-44 and optimizing the laser-proton source, producing 50 MBq of scandium-44 would require 25,000 laser shots. Assuming a laser repetition rate of 10 Hz, the total irradiation time would be ~2500 s (42 min) — a feasible duration for medical isotope production.

Future directions with lasers

Today, the lasers used to validate such a strategy for radioisotope production are based on titanium sapphire technology and provide a peak power in the range of a petawatt, i.e., 25 J at 25 fs, and a repetition rate limited to few hertz. Such laser technology offers flexibility both in terms of energy (from 1 to 25 J) and pulse duration (from 25 fs up to 5 ps), which allows a broad range of parameters and nuclear reactions to be investigated depending on the radioisotopes that must be produced. This high flexibility is crucial in the exploratory work to cover a broad range of parameters and identify, for commercial exploitation purpose, the trade-off between radioisotope productivity, technical maturity, and cost effectiveness compared with current solutions.

Therefore, as explained earlier, the need for sufficient radioisotope production not only requires the conversion efficiency between the laser pulses and the activity in megabecquerel per shot to improve, but also the laser repetition rate. If petawatt lasers operating at a few hertz are widespread, only a few have been demonstrated at 10 Hz. Operating at such repetition rates requires new strategies to manage the heat of the pump lasers and the main amplifier of the laser chain. For example, the ELI-BL petawatt system L3 HAPLS (High-Repetition-Rate Advanced Petawatt Laser System) developed at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California is pumped by a custom neodymium diode-pumped laser to reach 490 TW at 3.3 Hz. The Extreme Photonics Application Centre (EPAC) in the U.K. will use its internally developed ytterbium DIPOLE laser to pump its future 10-Hz petawatt laser, and Amplitude developed its 50-J 10-Hz neodymium flash-pumped laser to demonstrate 700 TW at 10-Hz operation.

In the meantime, more recent technologies based on direct-diode pumping constitute attractive solutions as they bring the promise of higher efficiency and lower complexity, provided that the laser parameters they can produce, mainly longer pulse durations, are compatible with efficient radioisotope production. Direct-diode pumping of ytterbium-, neodymium-, or even thulium-based materials bring the potential to provide kilowatt-class laser drivers for radioisotope production and other applications. The quest for inertial fusion energy production could significantly fuel these technological developments.

Future targets and diagnostics

The effective implementation of laser-driven radioisotope production will require both high-repetition-rate laser systems and corresponding advancements in target technology and diagnostics. A key challenge lies in the fact that the proton-generating pitcher targets are destroyed with each laser shot and must be replaced at the same rate as the laser pulses. Several potential solutions are currently under investigation.

One approach involves the use of a rotating target system, such as a wheel with multiple preloaded thin foil targets. The primary difficulty here is achieving precise synchronization between the laser pulses and the wheel’s rotation, ensuring that each laser shot accurately strikes a target foil rather than the supporting structure. An alternative method employs a continuously moving tape target, although maintaining the integrity of the thin foils remains a challenge, because they may easily break under the combined action of the tension exerted during sliding and the laser action. A third possibility is the use of a thin liquid jet as a renewable target medium. Regardless of the chosen approach, an additional technical hurdle is the efficient removal of debris from the vacuum chamber to maintain stable operation.

Furthermore, high-repetition-rate diagnostics will be essential to monitor both the laser-plasma interaction and the subsequent radioisotope production in real time. The development of such diagnostic tools, alongside innovative target delivery systems, is crucial for advancing laser-driven medical radioisotope production from a proof-of-concept stage to a viable and scalable technology.

Addressing all these challenges within a dedicated technological framework — accompanied by necessary funding — will be a critical step toward the widespread adoption of this novel production method.

Meet the authors

Antoine Courjaud works in strategic business development, secondary sources for medical and energy at Amplitude Laser. He has a Ph.D. in physics from the Centre Intense Lasers and Applications (CELIA); email: acourjaud@amplitude-laser.com.

Dimitri Batani is a professor at the CELIA laboratory at the University of Bordeaux, conducting research in plasma physics. He has a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Pisa. He also worked as a senior researcher and associate professor in the plasma physics group at the University of Milano Bicocca; email: Dimitri.batani@u-bordeaux.fr.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of CLPU for the support in realizing the experiments with the laser VEGA. This work was developed in the framework of the COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Action CA21128 PROBONO (PROton BOron Nuclear Fusion: from energy production to medical applicatiOns).

References

1. R.A. Snavely et al. (2000). Intense High-Energy Proton Beams from Petawatt-Laser Irradiation of Solids. Phys Rev Lett, Vol. 85, No. 14, pp. 2945-2948.

2. J. Bonvalet et al. (2021). Energetic α-particle sources produced through proton-boron reactions by high-energy high-intensity laser beams. Phys Rev E, Vol. 103, No. 5-1, p. 053202.

3. K.L. Batani et al. (2025). Generation of radioisotopes for medical applications using high-repetition, high-intensity lasers. High Power Laser Sci Eng, Vol. 13, p. e11.