Into the Quantum Domain, Versatile Lasers Are Enabling an Era of an Emerging Technology

Vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting lasers offer a scalable solution that is necessary to support burgeoning quantum applications.

By Philip Makotyn, Mircea Guina, and Jussi-Pekka Penttinen

The vibrant quantum technology space is characterized by a seemingly impossible superposition of contradictory facts. In one sense, quantum technologies have arrived: Cutting-edge optical atomic clocks are enabling solutions for position,

navigation, and timing systems, and atomic magnetometers used in oil and gas exploration are available today in the marketplace. On the other hand, other quantum technologies are still being developed, including quantum computers. Future large-scale quantum computers promise disruptive applications, most notably breaking modern cryptography standards. And at the same time, quantum networks have been deployed with the future aim of a quantum internet or un-hackable communication channels.

Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

Quantum is both fact and hype. Pioneering scientific advancements in quantum have featured on the front page of the New York Times and are (or support) the core science of many Nobel laureates. Yet quantum has also been a central theme in Hollywood blockbusters. Amid this dynamic, or as a result of it, large-scale investments from government and the private sector are driving incredibly fast progress in both research and technology development.

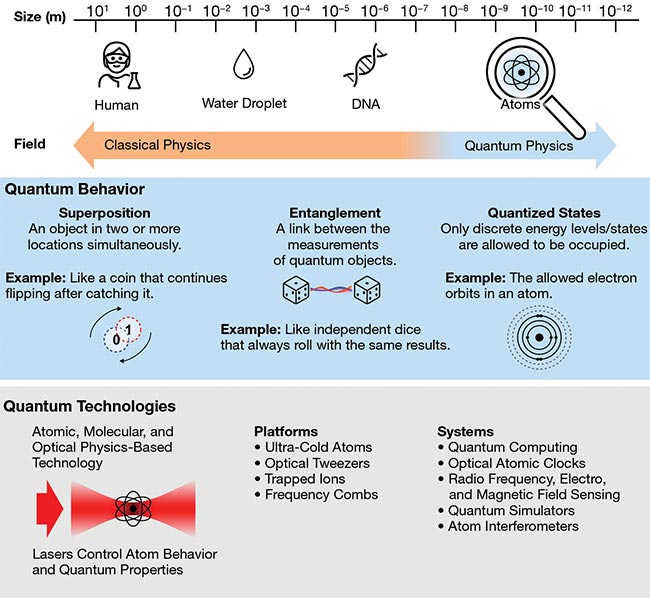

Quantum draws such considerable interest because of the nonintuitive laws that define the “quantum” behavior of

objects of atomic scale. The laws of physics at atomic scales are vastly different from the familiar science that describes the macroscopic “classical” world. Properties such as superposition, in which objects are simultaneously in two or more places; entanglement, when the outcomes of measurements are connected; and wave-particle duality, a behavior that describes existence as both a wave and a particle, are among the foundations of quantum theory. In fact, quantum theory is so nonintuitive that Einstein famously never fully accepted all of quantum theory. His quotation, “God does not play dice with the universe,” is often cited in various settings. Nevertheless, time and time again, experiments have demonstrated the quantum mechanical nature of the universe at microscopic scales.

Quantum technologies

The development of quantum technologies is roughly separated into two categories, with two distinct characteristics. Following the discovery of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, the Quantum

1.0 era uses the understanding of quantum rules in the development of technologies. For example, the internet is built upon a foundation of telecommunication lasers exploiting the quantization of energy levels. In contrast, the quantum computers, quantum sensors, and quantum networks of Quantum 2.0, coined in 2002, are technologies that directly engineer quantum states (Figure 1)1.

Figure 1. A description of quantum behavior and atomic, molecular, and optical technology platforms. At small scales, the behavior of objects is described by quantum theory rather than classical physics. Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

Quantum sensing, quantum computing, and quantum networking are the three main categories of Quantum 2.0 technologies. Quantum sensing uses the sensitivity (or insensitivity) of quantized energy levels to environmental conditions; the sensors can achieve unprecedented precision in measurements, supporting applications such as mineral exploration, medical imaging, and navigation in GPS-denied environments. Quantum computing relies on superposition and entanglement to

enable computations that are impossible for classical computers. Using qubits instead of classical bits, quantum computers offer the potential to revolutionize many industries and sectors. Quantum networking aims to enable secure communication and distribute quantum information, paving the way for a quantum internet.

The emerging Quantum 2.0 technology capabilities promise transformative solutions to climate change, drug discovery, personalized medicine, precision agriculture, and more accurate global positioning systems. The wealth of potential applications, with further possibilities, contributes to the expectation of quantum’s growth into a cross-vertical trillion-dollar industry.

Such a growth forecast shines a light on the foundational role of physical science as a key enabler to these quantum technologies and their applications. Various physical systems are used to access quantum states, each with advantages and disadvantages. To this end, a leading platform for engineering quantum technologies is atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physics-based systems, or simply atomic-based technologies. AMO quantum technology controls quantum behavior by shining laser beams on atoms, ions, or molecules.

As a result, the advent of lasers revolutionized the field of AMO quantum

research. As research moved away from dye lasers or other early light sources, reliable and performant lasers sparked immense progress and capabilities in AMO-based quantum technologies.

Today’s laser systems are tasked with

sustaining this growth in support of a rising number of applications.

Lasers: The main tool in the toolbox

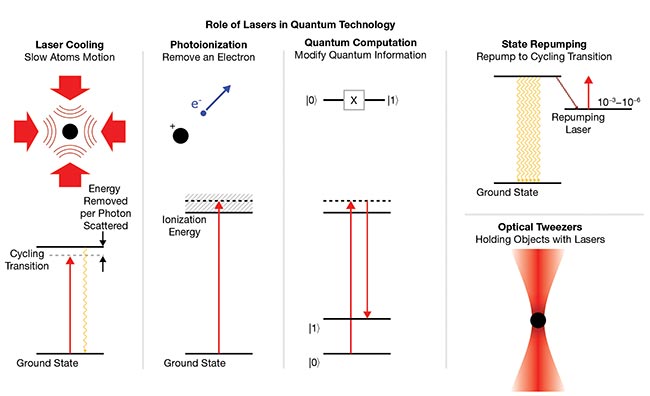

Due to the complex nature of interactions between light (photons) and atoms, lasers play multiple roles in atomic systems. Laser light is used for controlling particles, typically atoms, and interacting with quantum information — typically stored as properties of orbiting electrons. These operations are themselves broken down into categories. These include trapping atoms; cooling atoms (slowing their motion); the photoionization of atoms into ions with attractive quantum properties; quantum information operations; measuring a quantum state; and/or creating optical atomic clocks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The various roles of a laser’s function in quantum technologies. The electromagnetic field can be used to control the entire atom by slowing down its motion, or to control the quantum state of an electron. Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

Each of these roles requires distinct laser properties that, in some cases, may require many wavelengths for a single atomic species. In many cases, power, linewidth, and/or modulation performance are essential parameters. As a result, when building quantum systems, lasers are either controlled with built-in capabilities or externally modulated to meet requirements. For example, to improve beam quality and pointing stability, beams are often fiber coupled — in some systems for <1 m. Absolute frequency stability is achieved by locking light to an atomic reference, a self-referenced frequency comb, or an ultra-stable cavity.

Even as the maturation of laser technology earns praise, many limitations of atomic-based quantum technologies are ascribed to lasers with low power, high noise, wavelength limits, poor practicality, or a combination of these characteristics. In addition, there is not a consensus regarding atom species for quantum

sensing or computing technologies — every atom requires unique wavelengths, and this presents a challenge to the development of laser platforms. On the other hand, the development of versatile, better-performing lasers that offer, for

example, better wavelength coverage, would advance an increasing number of future applications.

Against this dynamic backdrop, optically pumped vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VECSELs) have emerged as a practical tool for quantum technologies, pioneered with trapped-

ion quantum computers and optical atomic clocks. Building on a legacy of VECSEL technology development since 2005, a collaboration between the Opto-

electronics Research Centre, Tampere University (Finland), and the National Institute for Standards and Technology demonstrated the benefits of optically pumped VECSELs in atomic-based quantum, ultimately leading to these semiconductor lasers being applied across a broad range of wavelengths to address numerous distinct quantum atomic technology platforms1.

A solution for quantum

From a photon’s perspective, a VECSEL, sometimes referred to as an optically pumped semiconductor laser (OPSL) or semiconductor disk laser, is like any other semiconductor laser. VECSELs are made up of III-V semiconductor quantum wells with specific energy levels engineered through design and epitaxy. By adjusting the composition of the semiconductors that form the gain structure, the output wavelength can be tailored in a broad range, typically extended from visible to beyond 2100 nm2.

An important aspect of the gain structure is the integration of a Bragg reflector at one end of the laser cavity. The other end of the cavity is defined by an external mirror, which can be also equipped with a piezo-electric element to tune the cavity length and stabilize the operation. The cavity can incorporate spectral filtering elements, such as birefringent filters or etalons, and optional nonlinear optical elements for frequency conversion. Other important elements instrumental for VECSEL operation are precise temperature stabilization of the gain medium and pumping the semiconductor gain, which is ideally achieved using robust and inexpensive high-power laser diodes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. An architecture of a vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting laser (VECSEL). Optical elements include precise temperature stabilization. The laser system architecture commonly includes a Bragg reflector, integrated with the gain chip, and an external mirror. Additional elements may include those for filtering, such as birefringent filters and/or etalons. Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

VECSELs emit light that is perpendicular to the surface of the chip, enabling symmetric optical pumping of the gain medium and generating an excellent

spatial mode. In contrast, edge-emitting laser diodes or amplifiers exhibit an asymmetric spatial mode due to the asymmetric waveguide geometry for guiding the light. Long photon lifetimes and high intracavity powers, owing to high-reflectivity mirrors, allow for stable and efficient intracavity frequency conversion — for example, second-harmonic generation — and as a result an easy and efficient path to expanded wavelength coverage.

Specifically for quantum systems, VECSELs provide several essential characteristics. These lasers simultaneously offer high output powers, broad wavelength selection, single-mode operation, and low noise. These features, achieved inherently through the VECSEL architecture, further enable trade-offs in performance specifications through gain and/or cavity engineering. The deployment of quantum technologies often requires

several or all of these characteristics for current or next-generation systems.

High output power, which is achieved via a large emission area and efficient thermal management, is a common requirement in atomic technologies — nearly every AMO system will benefit

from higher-intensity beams. For

example, optical tweezers used in optical atomic clocks and/or neutral atom quantum computers hold atoms tighter with increased laser power. Tighter and deeper traps are created from larger optical

powers and larger electric fields, through a phenomenon known as the AC Stark shift. Alternatively, higher laser powers reduce errors in neutral-atom or trapped-ion quantum computing logic gates through an interplay of error contributions from laser power, detuning, and technical noise. Increases in laser power in these settings serve to directly improve performance of quantum compute — an application for which a main limitation

stems from errors in computing operation(s).

Wavelength versatility is one of the most demanding laser requirements in atomic-based quantum technologies. The diversity of atom species used by hardware developers demands the use of lasers across a broad range of wavelengths. Further, the lack of consolidation to a single or few atomic species results in a broad spectrum of needed high-power single-mode lasers, from ~250 nm to 3 µm. Demonstrating how VECSELs are a solution to wavelength needs, the uncorrected images in Figure 4 show a rainbow of visible VECSEL outputs, from the broader available range of ultraviolet to near-infrared and into the shortwave infrared. The wavelength versatility of VECSELs through epitaxy design makes it possible to select practically every wavelength needed to drive atomic transitions.

Figure 4. Uncorrected images of high-power single-mode laser output demonstrating the wavelength versatility of vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VECSELs) (above). Atomic-based quantum technologies require a broad wavelength spectrum of high-power single-mode lasers. VECSELs address the requirement, emitting from the ultraviolet into the infrared. Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

Lasers with narrow linewidths and low noise are also critical among specific quantum operations. Optical atomic clocks and other quantum systems require ultra-stable sources with narrow linewidths. VECSELs can be easily locked to an atomic reference using the external cavity mirror piezo and narrowed to sub-hertz linewidths with an intracavity electro-optic modulator. Low-noise optical pumps and external cavity filtering can result in best-in-class amplitude and phase noise, critical for many quantum sensors as well as neutral-atom and trapped-ion quantum computers.

Practical and scalable architecture

The commercialization of quantum

systems and devices is occurring as many of these next-generation quantum technologies are also transitioning from laboratory settings into real-world environments. For example, optical atomic clocks have been deployed on ships participating in naval demonstrations. And quantum antennas and magnetometers are under development to be deployed on helicopter platforms.

VECSELs have several inherent advantages as an enabling technology when considering developing deployable quantum technologies. The laser architecture features a minimalistic number of elements and cavity design, while still meeting wavelength versatility and power scaling capabilities, avoiding the need for external amplifiers and doubling cavities. Similarly, as quantum computing transitions to data centers, VECSELs have the potential to offer a best-in-class size, weight, power, and cost metric needed for future at-scale quantum computing (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A compact vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting laser (VECSEL) designed to address the scaling needs of quantum computers and the environmental needs of quantum sensors. A reduction in size is due to the inherent advantages of a laser architecture that uses a minimalistic number of elements and simple cavity design. Broadly, VECSELs are an ideal platform to address the scaling needs of quantum systems. Courtesy of Vexlum Ltd.

From these benefits and ongoing innovation, VECSELs have emerged as a powerful and versatile tool for a variety of quantum applications; their inherent flexibility makes them viable solutions for many types of systems while enhancing stability and efficiency. As advancements in design and performance continue, VECSELs’ role in driving the future of quantum research and applications is set to expand, enabling future breakthroughs in fundamental science and real-world technologies.

Meet the authors

Philip Makotyn is president of Vexlum US, a subsidiary of Vexlum Ltd. He has more

than 15 years of experience in quantum technologies and earned a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Colorado; email: philip.makotyn@vexlum.com.

Mircea Guina is chairman, chief science

officer, and cofounder of Vexlum Ltd. He is also a professor of semiconductor technology at Tampere University, where he leads the Optoelectronics Research Centre; email:

mg@vexlum.com.

Jussi-Pekka Penttinen is the chief executive officer, chief technical officer, and cofounder of Vexlum Ltd. He has more than 15 years of experience in optically pumped VECSELs and is a leader in the field; email: jp@vexlum.com.

References

1. S.C. Burd et al. (2016). VECSEL systems for the generation and manipulation of trapped magnesium ions. Optica, Vol. 3, No. 12,

pp. 1294-1299.

2. M. Guina et al. (2017). Optically pumped VECSELs: review of technology and

progress. J Phys D:Appl Phys, Vol. 50,

p. 383001.

/Buyers-Guide/Vexlum-Ltd/c32709