Hearing aids, mouth guards, dental implants, and other highly tailored structures are often products of 3D printing. These structures are typically made via vat photopolymerization, and the process also involves printing structural supports from the same material to hold the product in place as it’s printed. Once a product is fully formed, the supports are removed manually and typically thrown out as unusable waste.

MIT engineers have developed a way to bypass this last finishing step, in a way that could significantly speed up the 3D-printing process.

To achieve this, the researchers developed a resin that turns into two different kinds of solids, depending on the type of light that shines on it: Ultraviolet (UV) light cures the resin into a highly resilient solid, while visible light turns the same resin into a solid that is easily dissolvable in certain solvents.

The researchers exposed the resin simultaneously to patterns of UV light to form a sturdy structure, as well as patterns of visible light to form the structure’s supports. Instead of having to carefully break away from the supports, they simply dipped the printed material into solution that dissolved the supports away, revealing the sturdy, UV-printed part.

These supports can dissolve in a variety of food-safe solutions, including baby oil. Interestingly, the supports could even dissolve in the main liquid ingredient of the original resin, like a cube of ice in water. This means that the material used to print structural supports could be continuously recycled: Once a printed structure’s supporting material dissolves, that mixture can be blended directly back into fresh resin and used to print the next set of parts along with their dissolvable supports.

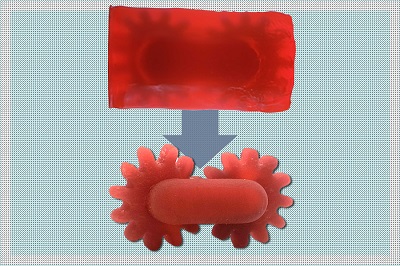

They applied the method to print complex structures, including functional gear trains and intricate lattices.

Researchers developed a resin that turns into two different kinds of solids, depending on the type of light that shines on it: Ultraviolet light cures the resin into a highly resilient solid, while visible light turns the same resin into a solid that is easily dissolvable in certain solvents. Courtesy of MIT News.

The work offers a streamlined approach to widely used vat photopolymerization by targeting the necessary supports. Conventional vat photopolymerization begins with a 3D computer model of a structure to be printed, for instance, of two interlocking gears. Along with the gears themselves, the model includes small support structures around, under, and between the gears to keep every feature in place as the part is printed. This computer model is then sliced into many digital layers that are sent to a vat photopolymerization printer for printing.

A standard vat photopolymerization printer includes a small vat of liquid resin that sits over a light source. Each slice of the model is translated into a matching pattern of light that is projected onto the liquid resin, which solidifies into the same pattern. Layer by layer, a solid, light-printed version of the model’s gears and supports forms on the build platform. When printing is finished, the platform lifts the completed part above the resin bath. Once excess resin is washed away, a person can go in by hand to remove the intermediary supports, usually by clipping and filing, and the support material is ultimately thrown away.

The team looked for a way to simplify and speed up the removal of printed supports and, ideally, recycle them in the process. Team members came up with a general concept for a resin that, depending on the type of light that it is exposed to, can take on one of two phases: a resilient phase that would form the desired 3D structure and a secondary phase that would function as a supporting material but also be easily dissolved away.

The team members found that they could make a two-phase resin by mixing two commercially available monomers, the chemical building blocks that are found in many types of plastic. When UV light shines on the mixture, the monomers link together into a tightly interconnected network, forming a tough solid that resists dissolution. When the same mixture is exposed to visible light, the same monomers still cure, but at the molecular scale the resulting monomer strands remain separate from one another. This solid can quickly dissolve when placed in certain solutions.

In benchtop tests with small vials of the new resin, the researchers found the material transformed into both insoluble and soluble forms in response to UV and visible lightly. But when they moved to a 3D printer with LEDs dimmer than the benchtop setup, the UV-cured material fell apart in solution. The weaker light only partially linked the monomer strands, leaving them too loosely tangled to hold the structure together.

The researchers found that adding a small amount of a third “bridging” monomer could link the two original monomers together under UV light, knitting them into a much sturdier framework. This fix enabled the researchers to simultaneously print resilient 3D structures and dissolvable supports using timed pulses of UV and visible light in one run.

John Hart, MIT professor of mechanical engineering, said, “We’ll continue studying the limits of this process, and we want to develop additional resins with this wavelength-selective behavior and mechanical properties necessary for durable products. Along with automated part handling and closed-loop reuse of the dissolved resin, this is an exciting path to resource-efficient and cost-effective polymer 3D printing at scale.”

This research was supported, in part, by the Center for Perceptual and Interactive Intelligence (InnoHK) in Hong Kong, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Office of Naval Research, and the U.S. Army Research Office.

This research was published in Advanced Materials Technologies. (www.doi.10.1002/admt.202500650)